Alleged Errors of Scientific Primitivism

Science traditionally is any branch of knowledge or study. The word is from the Latin scientia, which just means “knowledge.” In the modern era, the word came to mean only the physical, or material, sciences that study physical phenomena, whether astronomy, biology, chemistry, geology, or physics. The natural sciences study how nature behaves. It examines various kinds of cause and effect by inductive reasoning from empirical observation. The questions of whether there is such a thing as Supernature, or whether there may be supernatural causes on the plane of nature, are two questions that the natural sciences cannot examine by empirical means.

When it comes to any overlapping fields between Scripture and science, Richard Gaffin writes that,

“the reciprocal relationship that marks these two ‘books’ and their study is asymmetrical. Scripture, not nature, always has priority in the sense that in it God reveals himself, as the Belgic Confession also says, ‘more clearly and openly, particularly on matters basic to our identity as human beings and our relationship to him.”

In that vein, Gaffin adds,

“where Scripture speaks incontrovertibly on a matter, if science reaches contrary findings, it should be prepared to question them, no matter how apparently certain those findings.”1

This has not been the prevailing sentiment among modernist theologians. Typical of this trend was nineteenth century biblical scholar Franz Delitzch, who wrote, “All attempts to harmonize our biblical story of the creation of the world with the results of natural science have been useless and must always be so.”2 The birth of modern “biblical scholarship” also happened to coincide with the rise of scientism. There is no coincidence, then, that those “Christian scholars” who are quickest to lap up the propaganda of Babylon’s state-enforced “scientific consensus” are usually the people who know the least about science and who also happened to rarely be believers in supernaturally revealed Christianity.

The Creation Account

Virtually all of the questions about texts from the early chapters of Genesis are going to be answered differently, according to the view one holds on how to interpret Genesis 1 in particular. There is:

(1) the Young Earth or, 6 24-Hour Days View;

(2) the Old Earth or, Day-Age view;

(3) Framework Hypothesis;

(4) Augustine’s Instantaneous Creation View;

(5) Gap Theory.

We need to at least be aware of the differences between these views when we are reading responses to criticisms of the Bible. Each of these is claiming to be a Christian account of things. It may be that the answers that one of these models offers does not exhaust the possible answers that could be given.

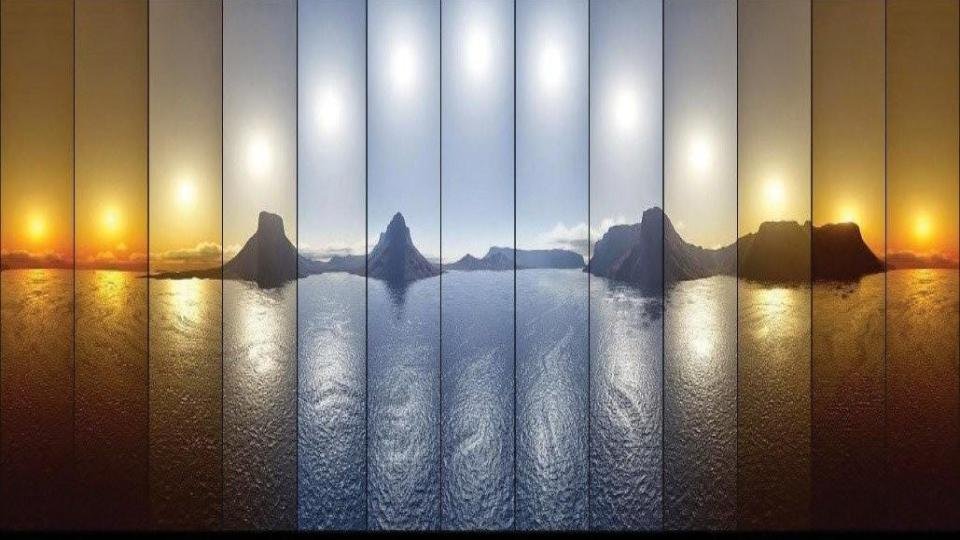

Perhaps the first understandable criticism that comes up in the Genesis text has to do with light. We see that light is created on Day 1 (1:3) and yet the sun, moon, and stars are created on Day 4 (1:14-18). The difference between the light source in Day 1 versus Day 4 is handled differently in the Old Earth and Young Earth models.

In the Old Earth (hereafter called OE) model, each day of Genesis 1 represents an age. Thus the other name for this is the “Day-Age” view. Accordingly, while Day 1 would represent the beginning of the formation of our solar system, with the sun at the center, Day 4 takes us to a stage of earth’s development where that same light is now visible, through the atmosphere. Since the perspective of Moses is earth-bound (and since he is not offering us a scientific textbook in the modern sense), it is sufficient for him to use this phenomenological language of what appears to him as “two lights,” but which is really outworking of the first.

In the Young Earth (hereafter called YE) model, each day is a literal 24-hour period. The light of Day 1 was God’s own glory, later referred to as the Shekinah glory, which he could manifest to human beings. A hint of this divine light in creation is found in Revelation 21:23. To suppose that this does not “explain” any light required for Moses to see or for plants to live in the intervening period would be an exercise in special pleading, given the power of God and the shortness of that period between Days 1 and 4. Regardless of which model is correct, why would an omniscient God inspire Moses to write something that he knew would perplex modern readers? The answer lies on the flip side of that coin. It is the task of readers (in any age) to interpret texts in their own cultural context. Moses had no interest in settling disputes of modern cosmology, but one of ancient idolatry.

A close second to that specific objection is another concerning plant life. Chapter 2 seems to have no plant life until Adam was formed, yet Chapter 1 says it was made on Day 3. The most important piece of context in all proposed resolutions is to note that Genesis 1 is what may be called the “cosmological” account and Genesis 2 the “anthropological” account of creation.

In other words, Chapter 2 provides a kind of zoomed-in instant replay of sorts to Day 6. In that second account, the focus on Adam’s vocation is only that the vegetation became cultivated at this time.

The Hebrew of 1:11-12 speaks of “seeding a seed” (מַזְרִ֣יעַ זֶ֔רַע) and “grass” (דֶּ֔שֶׁא), whereas the word for “bush” (שִׂ֣יחַ) used in 2:5 differs, and it is reasonable to take them as the cultivated version of the plants first created on Day 3. When understood in this context of Adam “as gardener,” the two passages fit perfectly. Chapter 1 (Day 3) shows God creating all plant life at its basic level, and Chapter 2 (verse 5) zooms in to the beginning of the human cultivation of that plant life.

In our response to the JEDP Theory we had to field the objection that Chapter 2 appears to be some sort of duplication that a later redactor made conflict with Chapter 1. In that theory, the focus was on the divine names. But then it will also sometimes be asked whether or not there are two first couples. Here again, the distinction to observe is that between the “cosmological account” (Genesis 1) and the “anthropological account” (Genesis 2). In other words, they are the same events, with the same man and woman. However 1:26-27 sets man and woman in the larger spatial context of God’s creation of the whole universe, whereas 2:15 and 2:20-24 sets the man and woman in the more local stage of this world. Each has its own purpose. Think of the second chapter as a kind of “instant replay” where a closer angle shows man’s vocation at tending to the Garden and the woman’s role as a helper for him.

The Flood and Antediluvian Ages

There have been two basic approaches to examining geological data: catastrophism and uniformitarianism. Catastrophism explains the data from the standpoint that there have been a number of sudden upheavals or “catastrophes” (e.g. the Flood) in the earth’s surface, atmosphere, and topography. Uniformitarianism explains the data as if the processes have been uniform throughout earth’s history. In the words of one of its founders, “the present is the key to the past,” since the rates of change now have been steady throughout.

Several flood objections are what we might call “feasibility” or “sensibility” objections. For instance: If others had boats, why didn’t they survive? The Flood is described as something that is a bit more than “a lot of water.” We are talking about the explosion of the subterranean depths that would have involved a lot of shifting of terrain, high temperatures, and other things that go beyond even what we see of Flood images today that can easily topple well constructed and large ships.

Several problems are more specifically difficult for either the YE-Global Flood view, or the OE-Local Flood view. For instance, the denial of a global flood seems to run contrary to the clear language of universal judgment,

“For behold, I will bring a flood of waters upon the earth to destroy all flesh in which is the breath of life under heaven. Everything that is on the earth shall die” (Gen. 6:17).

It also seems to violate common sense principles of nature such as that water seeks its lowest plane. In other words, even a large local flood would either run itself outward or else demand as much of a radical change of earth’s topography as anything catastrophists propose. On the other hand, the affirmation of a global flood that immediately shifts the continents to their present place involves the problem of land bridges for both animal life and populations that migrated to the “new world,” such as the Native Americans.

As far as a “necessity” of rapid evolution to account for the diversity of species we see today, this is not so insurmountable as it may seem at first. There is no reason, on the surface of things, to restrict God from being able to raise and re-cultivate living organisms in the creation after the Flood as he did in the original. Of course if someone makes this argument, they will be appealing to miracles (of which the Scriptures say nothing of at that point). So it is a question of drawing inferences and determining which inference is more in keeping with the whole of the biblical data. But the idea that it is impossible is not really a scientific, but philosophical, statement. But this would also be worth remembering when someone brings up why either fish or insect life would be exceptions to God’s universal judgment.

We could also add to this section on the Flood features of that age, especially the ages of the antediluvians. For example, we read:

“And all the days that Adam lived were nine hundred and thirty years: and he died” (Gen. 5:5); “And all the days of Seth were nine hundred and twelve years: and he died.” (Gen. 5:8). “And all the days of Methuselah were nine hundred sixty and nine years: and he died” (Gen. 5:27).

There are two possibilities, naturally, depending on whether one takes an old earth or young earth view. The OE view will say that there are “open genealogies” (which can be read about in various authors) but also that the numerical values are symbolic. In the YE view they are quite literal and are explained partly by the change in the earth’s environment from prior to the Flood versus after. It may also be (in such a model) that it is direct divine judgment and needs no appeal to that natural circumstance.

Miscellaneous “Material Mistakes”

Perhaps the most infamous of these is that of the mustard seed. Jesus calls it “the smallest of all the seeds on earth” (Mat. 13:31; Mk. 4:31; Lk. 13:19). The short answer to this is that Jesus was speaking proverbially; and the fact that He uses “mustard seed” in a clearly figurative way elsewhere solidifies this point.

“He said to them, ‘Because of your little faith. For truly, I say to you, if you have faith like a grain of mustard seed, you will say to this mountain, ‘Move from here to there,’ and it will move, and nothing will be impossible for you” (Mat. 17:20; cf. Lk. 17:6).

In that region, this seed really was the smallest of the garden seeds—which is what it was being compared to in the parable. Even of other kinds of plants in Israel at that time, the mustard tree did not grow to literally be the biggest. The olive tree would be bigger, and Jesus would have been very familiar with that.

This is an example of using superlative speech in a sense that is restricted by the point one is making, such as when we say that so and so was “the greatest of all time” or that “things have gone from bad to worse,” and countless other examples. We do not expect people to pedantically break into such conversations and challenge what is obviously relative language that uses superlatives in a restricted sense. On the contrary, we use words like “pedantic” to describe people who do have such fixations. But no actual untruth has been spoken because the truth of statements has respect to the exact claim being made.

A few from Leviticus are a common target. Our first clue should be the close proximity of these, in Leviticus, which is giving us what? Primarily we are having revealed ceremonial law. That is a crucial context.

First, it says here that the badger and the rabbit “chew the cud” (11:5); and yet they do not regurgitate their food in the way that we would mean this. Interestingly the verse that functions as a “header” to the section (v. 3) says, “Whatever parts the hoof and is cloven-footed and chews the cud, among the animals, you may eat.” In other words, two signs external to these animals are given to Israelites.

Geisler and Howe then complete our picture of what is actually going on:

“It is known that rabbits practice what is called “refection,” in which indigestible vegetable matter contains certain bacteria and is passed as droppings and then eaten again. This process enables the rabbit to better digest it. This process is very similar to rumination, and it gives the impression of chewing the cud. So, the Hebrew phrase “chewing the cud” should not be taken in the modern technical sense, but in the ancient sense of a chewing motion that includes both rumination and refection in the modern sense.”3

The Hebrew words will not allow that level of specificity in the first place. The word rendered “chew” actually comes from the same verb as “to ascend” or “go up” (alah), so although the noun for “cud” (gerah) is only used in this context of the food laws, the point of the description is a way for speaking of the outward or visible motion.

The Israelites were not being commissioned to write a zoology manual; they were being summoned to assemble before God in purity. With that context, consider whether a bat is a bird. Leviticus 11:19 classifies the bat together with nineteen other species under the genus of “birds” (v. 13). Again, the Israelites were not doing modern taxonomy; they needed to know to stay away from those flying things. The Hebrew word עוֹף functioned generically as “flying creatures.” Hence what was communicated here was on a “need to know” basis.

One supposedly material mistake is actually of a mathematical kind. We can call it “the pi objection.” 2 Chronicles 4:2 tells us, “Then he made the sea of cast metal. It was round, ten cubits from brim to brim, and five cubits high, and a line of thirty cubits measured its circumference.” Let us remember Frame’s point about the distinction between truth and precision, and what I called the “fallacy of precisionism.”

Matt Slick explains this here,

“First of all, the Bible is not intended to be a scientific book on geometry. Second, the inside of the bowl could have been 10 cubits while the outside diameter was 31.4159 cubits. Third, it was a common practice in the Bible to give rounded numbers to represent the whole.”4

He then lists four examples of such rounding off in Old Testament passages that most skeptics would not be bothered by in the least.

Other examples of “primitivism” may not be actual conflicts with modern science, but being regarded by moderns as “superstitions,” still fit under the same category. For example, Exodus 34:26 and Deuteronomy 14:21 forbid boiling a goat in its mother’s milk. In addition to being rather cruel, this seems altogether mindless. If you examine ancient historical writings on Canaanite religion the idea developed that if an animal was sacrificed or boiled in its mothers milk then it would provide strength to the remaining flock. It was superstition and God did not want them engaging in these types of practices. They were to put their trust in God rather than witchcraft. This law was not teaching that boiling an animal in milk is always sinful rather it is about the motivation for doing so.

Perhaps the most favorite of such objections regards the mention of unicorns. It is true that the word “unicorn” appears in the King James Version nine times—in Numbers 23:22 and 24:8, Deuteronomy 33:17, Job 39:9,10, Psalms 22:21, 29:6 and 92:10 and in Isaiah 34:7. But no, this is not a claim to the winged horse with the horn of our imaginations. The Hebrew word represented in the King James Version by ‘unicorn’ is re’em (רְאֵם), which undoubtedly refers to the wild ox. The ESV and NASB for example handle this better for our modern understanding. This is somewhat typical of many Hebrew words, which can have multiple meanings. In most cases context makes it simple. When it comes to animals, there tends to be more trouble, as they are listed in groups and that can dilute context. One does not need to be an expert in Elizabethan English to figure out that this did not represent a belief in mythological creatures among the first few generations of English Bible readers.

Phenomenological Language

Phenomenological language is describing things as they appear. The word phenomenon just comes from the Greek word for appearances.

People who refuse to accept this will either believe things like the Bible teaching a flat earth, or else attack the Bible on that basis. Others will try to put this all to rest by finding Bible passages speaking of its roundness, such as Isaiah 40:22, which says, “It is he who sits above the circle of the earth”; or else Job 26:10, which says, “He has inscribed a circle on the face of the waters.” However, a very reasonable case can be made that “circle” here is merely picturesque for highlighting the transcendence of God over the earth in general and waters in particular. These are portions of Scripture that are steeped in figurative language.

Now if the Scriptures are not primarily a book on astronomy or geology, we should not be surprised that we will not find many of the kinds of proof-texts that would utterly confound the flat earth position. Phrases like “the four corners of the earth” in Revelation 7:1 and 20:8, much like “four winds of heaven” in Matthew 24:31, are expressions of totality. The one isn’t teaching that the earth has corners anymore than that its people inhabit the air of heaven. Likewise with “pillars of the earth,” are a poetic way of speaking of God’s providence upholding history and our lives. Just consider what pillars are. They are two columns made of stone.

Likewise Psalm 93:1 says that “the earth cannot be moved.” Does this deny that the earth rotates or revolves around the sun? No. Psalm 19:5-6 likewise speaks of the sun “running its course” across the sky. So here, do we have a flat and stationary earth? Again, no. One text speaks of immovability of the earth relative to man, and the other of the sun as an obedient soldier in relation to God’s command.

Miraculous as Mythological

In one sense, it is difficult to consider this class of objections as speaking about “error” in the same way. Most people recognize myth as a legitimate kind of literature. However, the modernist rejects miracles out of hand, and thus he either reduces miracles to myth, or else to plain old lies. However, the latter would more directly be a kind of error; and since the plain reading of the Bible’s claims to miracles are best understood as a genuine belief that such things happened, then, assuming that they did not, the skeptic would be saying that the biblical authors were wrong. Rather than saying they were lying, it is rather that they were misled. But this too comes to the same point. It is still a kind of error.

Hence Jonah and the whale, the miracles performed through Moses as judgments upon Egypt (Ex. 7-10), the parting of the Red Sea (Ex. 14:19-31), the floating ax head (2 Ki. 6:1-7), the miracles of Jesus and those performed by the Apostles, and of course the most central miracles of all—Virgin Birth and Resurrection—would all have to be understood as either myth or fable.

The case of the sun suspended in the sky for an hour (Josh. 10:12-13) is a good case study for how presenting alternative resolution can often be the best approach. Slick lists six possibilities for the meaning of these words in Joshua:

(1) poetic citation not meant to be literal — from the Book of Jasher, cf. v. 13; (2) not literal, but figurative to express that it did not set until the battle was won; (3) solar eclipse; (4) the appearance caused by the earth wobbling in its rotation [recorded instances cited]; (5) the sun appeared to stop but only for Israel; or else (6) the sun actually stopped, or the earth stopped its rotation.5

In some cases there really can be more natural explanations for phenomena, even where they are combined by things altogether supernatural. For example, is Numbers 21:6 talking about angels or fiery serpents? It is best to take the creatures in this passage as literal serpents. True, the adjective “firey” הַשְּׂרָפִ֔ים has the same root (שָׂרָף) as the root for those angels called “seraphim.” I cannot say why angels who are not fallen would share this same word, or what connotation if any is to be drawn. It may be that while serpents may preeminently symbolize the curse, literal serpents still serve God’s purpose. Consider for example Jesus’s statement to, “be wise as serpents” (Mat. 10:16).

All that to say that while God’s reasons for the link between those angels and the serpents may be filled with mystery, it is very appropriate to take the serpents in Numbers as literal, as they did signify the curse in Genesis 3:15 and Christ’s own taking of the curse (Gal. 3:13) in fulfillment of that very type (Jn. 3:13). In other words, our reason to prefer the “natural explanation” is very often for theological reasons spelled out elsewhere in Scripture rather than some misplaced reverence for modern sensibilities under the guise of “science.”

_____________________

1. Richard B. Gaffin Jr., No Adam, No Gospel (Phillipsburg, NJ: Presbyterian & Reformed Publishing, 2015), 8.

2. Franz Delitzch quoted in Hugh Ross, The Genesis Question (Colorado Springs: NavPress, 2001), 13.

3. Norman Geisler and Thomas Howe, When Critics Ask (Grand Rapids: Baker Books, 2002), 90.

4. Matt Slick, “The diameter of a bowl is mathematically incorrect” in Bible Difficulties (CARM Website).

5. Slick, “Did Joshua’s long day where the sun stood still really happen?” in Bible Difficulties (CARM Website).