Introducing the Covenant of Works

Christians of all traditions understand that God placed the first man, Adam, in a relationship to Him that was foundational for everything else that has happened in human history. Such may be conceived in purely genetic terms, or also in the sense of a moral pattern, or even as the origin of sin. The Reformed view encompasses all of these, but it is unique in articulating this primal position of Adam in a representative relationship standing in between God and the whole human race which issued from him.

At this point, we have one more lesson in etymology. In the Latin language, the word foedus means “pact” or “covenant.” It is from this word that we derive our English words “federate,” “federal,” “federation,” and “confederation.” Therefore, when Reformed theologians have described Adam in a covenantal relationship with God, they have also meant that he was placed in a federal (representative) position when it comes to the rest of us. It is often argued by those who hold to a mono-covenantal framework, that Calvin himself “only knew a covenant of grace.”1 Those following Karl Barth especially have argued that we cannot find any sort of covenant between God and man at creation.2

However, as Richard Belcher explains,

The implications of denying the covenant of works can be monumental for theology because the covenant of works lays a foundation for other key doctrines of Scripture, including the obedience of Christ, the relationship between Adam and Christ, and the concept of Christ as mediator. These ideas are important for a correct view of justification by faith and the imputation of Adam’s sin and Christ’s righteousness.3

Note carefully that Belcher is not claiming that if one does not “believe in” the covenant of works, that he cannot believe in any of these other truths at all. However, he is saying that one cannot have a more “correct view” of these matters that are so logically related to the covenant of works. In introducing this concept, we will examine this covenant’s reality, its naming, and its uniqueness.

The Reality of the Covenant

The biblical passage that introduces the covenant idea to us is Genesis 2. As one might expect, Genesis 1 will be necessary as background to the specific arrangement communicated to Adam. However Genesis 2:16-17, in particular is our central text.

And the LORD God commanded the man, saying, “You may surely eat of every tree of the garden, but of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil you shall not eat, for in the day that you eat of it you shall surely die.”

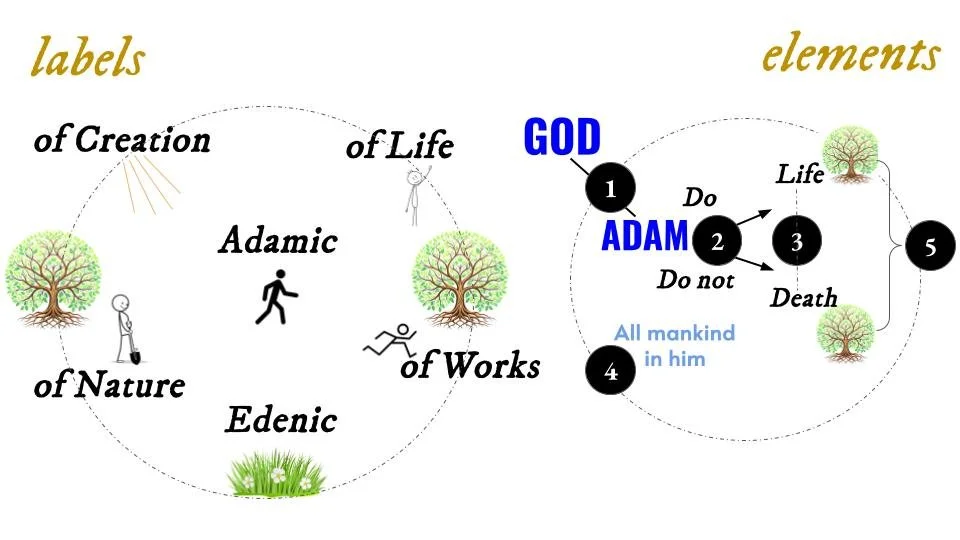

Perhaps the easiest thing to get from this passage—the thing that most parties would agree is taught here—is that God placed Adam, in a sense, between life and death, and that He did so by the pathways of obedience (unto life) or else disobedience (unto death). The simple contrasting words are ‘You may’ (v. 16) and ‘you shall not’ (v. 17).

Recall as well that the real standard for whether or not there is a covenant present in a biblical text is not simply whether the word is present, but whether the substance is there. And the substance is discovered by essential attributes or elements of the thing in question. What then were those elements of a covenant? Reformed theologians will typically point to five, and I will use Belcher’s list:

First, the two parties to the covenant are clearly identified … Second, covenants have conditions … Third, covenants have blessings and curses … Fourth, covenants operate on the basis of a representative principle … Fifth, covenants have signs that point to the blessings of the covenant relationship.4

Now on what exact basis in the text of Genesis 2, or beyond, do we maintain these five elements? The parties (God and Adam), conditions (obey or disobey), and then the threat of death are all as plain as day.

However, it may be asked where we find the blessing of life. Again, the curse of death is clear enough in verse 17, but where is there a promise of life? Roberts is in line with the main line of covenant theologians in saying that by “his explicit threatening of death in case of disobedience … [it] implicitly promises life in case of obedience.”5 Moreover, the presence of the tree of life, mentioned both before the fall (2:9) and after it (3:22), seems to suggest that this fruit was available at some point.

The representative principle is clearly taught by Paul in two places especially:

Therefore, just as sin came into the world through one man, and death through sin … many died through one man’s trespass … because of one man’s trespass, death reigned through that one man … by the one man’s disobedience the many were made sinners” (Rom. 5:12, 15, 17, 19).

For as by a man came death, by a man has come also the resurrection of the dead. For as in Adam all die, so also in Christ shall all be made alive (1 Cor. 15:21-22).

Support also comes from another Old Testament passage: “But like Adam they transgressed the covenant; there they dealt faithlessly with me” (Hos. 6:7). Regardless of the exact historical circumstances of the referent with Israel, the fact of the matter is that the analogy is to Adam’s transgression; but how could Israel’s transgression be likened unto Adam’s in the context of a covenant unless Adam was similarly in a covenant? It may be argued that the analogy is only with respect to the sin and not to the arrangement in which the sin took place. This seems to be an unnatural reading, when such a short statement bothers to include the covenant concept.

Others will suggest that name Adam is the generic word for man and therefore symbolic, and still others suggest that Adam is a place at which these people had similarly transgressed. To the first, we must ask: Symbolic of what? If it is to “mankind” in general it would be blunted of its force as addressing a personal guilt for particular sins. Besides, what covenant would this be that all mankind is under? It cannot be the same as the specific one Israel is in—and Israel is the other side of the analogy—and it cannot be a different one than Israel, for the whole point of the objection is to deny that there is one. As to the appeal to place, it refers to “Adam, the city that is beside Zarethan” (Josh. 3:16). Belcher remarks that, “no scriptural evidence of covenant breaking at Adam exists. Also, this view requires that the preposition before ‘Adam’ be amended from ‘like’ (כ) to ‘at’ (ב).”6

We will examine one more approach to establishing the reality of this covenant. Roberts gives four evidences that God entered into this covenant with Adam.

“(1) From the inscription of the Covenant of Works in Adam’s heart.”7 What does Roberts mean by this? He equates the covenant to the moral law. A detailed defense of that will have to wait; but for our purposes, it at least draws attention to the fact that Adam was under law from the beginning. Paul says it was written on the hearts of all mankind in Romans 2:14-15— though Roberts does not make this his leading rationale, reminding us that this work of the law in the heathen is “in some dim characters”8—but on what ground could Adam possibly be excluded from that? Covenants are many things, but they are at least a binding of the party to moral duties. Since the moral law consists in those duties woven into permanent fabric of man’s relation to God and man, it is logically impossible that Adam did not have the substance of moral law upon his heart.

“(2) From God’s express prescription of a positive law unto Adam in his innocent state.”9 This is that command of what trees Adam could and could not eat from. A law is called positive law if it is posited by God’s will in such a way that its objective nature is not of the permanent order of things. This is to be distinguished from natural law, which is also caused by God’s will, but regards the permanent nature of things. Some will speak of the difference between positive law and natural law as if the former is wholly “arbitrary,” in the contemporary sense of that word, so that there is no reason at all for God to have commanded the thing. There is a motive behind such a definition that is commendable. It seems as though the goal is to insist that we ought to always obey God whether we understand the reason or not, or whether any reason is ever given. That is certainly true. However, such a definition can run into several difficulties, not the least of which is to cast a shadow upon divine wisdom. It is best to stick to the language of permanent as opposed to alterable. The tree of the knowledge of good and evil is indeed mysterious—and it may well be that prying into that mystery is the very sin underneath the surface—yet even that consideration assumes a hint of reason. That there are hidden things that belong to the LORD our God (Deut. 29:29) shows both reason enough and reason indeed.

“(3) From the intention and use of the two eminent trees, namely, the tree of life in the midst of the garden, and the tree of knowledge of good and evil.”10 These two trees are treated symbolically and sacramentally. “And some are of the opinion that this tree signified Christ the Son of God, in whom was life, and that life was the light of men.”11

For example, Augustine,

So then the tree of life also was Christ, like the rock; and indeed God did not wish the man to live in Paradise without the mysteries of spiritual things being presented to him in bodily form. So then in the other trees he was provided with nourishment, in this one with a sacrament—a sign of what else but of the Wisdom of whom it is said, She is the tree of life to those who embrace her, just as it would be said of Christ that he was the rock pouring out water to those who thirsted for him?12

William Perkins said roughly the same.

Now for Adam’s sacraments, there were two: the Tree of Life, and the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil: these did serve to exercise Adam in obedience unto God: these did serve to exercise Adam in obedience unto God. The Tree of Life was to signify assurance of life forever, if he did keep God’s commandments: the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil, was a sacrament to show unto him, that if he did transgress God’s commandments, he should die: and it was so called because it did signify that if he did transgress this law, he should have experience both of good and evil in himself.13

“(4) Finally, from the sad event and fruit of the first Adam’s fall, to all his ordinary posterity, even all mankind: namely, guilt of sin and death.”14 For this, Roberts briefly paraphrases the words of Paul in Romans 5:12-21 that I have already cited.

The Naming of the Covenant

Not all Reformed theologians have agreed on that title. There have been other candidates. It has also been called the Adamic covenant (since that speaks of the party), or else the Edenic covenant (since that speaks of the place), or else the covenant of creation (speaking of the origin), or even the covenant of nature (speaking of its abiding quality in terms of the way things are), and, perhaps most surprisingly, the covenant of life (speaking of the reward Adam would have if he obeyed).

John Murray spoke of the “Adamic Administration,” objecting to “the language of a covenant of works, not only in that it militated against the gracious character of God’s covenanting with man, but also that it speaks of a prefall ‘covenant,’ whereas the Scriptures reserve the language of covenant to God’s postfall dealings with the sinful creature.”15 Murray is an oddity in this, being a Reformed covenant theologian and yet not wanting to even use the word “covenant” of this pre fall arrangement.16

Robertson opted for “the covenant of creation,” for one because, “By thinking too narrowly,” the Reformed “have come to cultivate a deficiency in [our] entire world-and-life view.”17 He had two other reasons:

To speak of a covenant of ‘works’ in contrast with a covenant of ‘grace’ appears to suggest that grace was not operative in the covenant of works. As a matter of fact, the totality of God’s relationship with man is a matter of grace … The terminology further suggests that works have no place in the covenant of grace. But from a biblical perspective, works play a most essential role in the covenant of grace. Christ works for the salvation of his people. His accomplishment of righteousness for sinful men represents an essential aspect of redemption. Still further, those redeemed in Christ must work. They are ‘created in Christ Jesus unto good works’ (Eph. 2:10).18

I said that “covenant of life” may seem most surprising to us, but the Westminster Larger and Shorter Catechisms themselves use the language:

The providence of God toward man in the estate in which he was created, was … entering into a covenant of life with him, upon condition of personal, perfect, and perpetual obedience, of which the tree of life was a pledge; and forbidding to eat of the tree of knowledge of good and evil, upon the pain of death (WLC Q20; cf. WSC Q12).

Francis Turretin used the words “nature … works … legal” to describe it,19 though he settled on “covenant of nature” as his section unfolded. Witsius, recognizing the use of the labels “nature” and “legal,” nevertheless opts for covenant of works.20

The main danger in using the label “covenant of nature” has been highlighted in more modern Reformed theology where the very concept of nature has been reduced to soteriology, and therefore the change in man’s states or “natures,” became inflated so that the subjective performances of man form the only concept remaining. The objective nature of things, whether external to man or the essence of man himself, is swallowed up in the focus of these four states of man—which are species of nature rather than its genus.

Gerhardus Vos was one modern Reformed theologian—and a biblical theologian at that—who seemed to understand the value of maintaining the distinction between the overarching creational (natural) relationship and covenantal (saving) relationship. This is also reflected in his maintaining the classical distinction between the essential and amissible image of God, but one must go back to the creative act and product. Vos wrote,

a) Adam by nature was obliged to obey God, without thereby having any right to a reward.

b) God had created him mutable, and he also possessed no right to an immutable state.

c) His natural relationship to God already included that he, if sinning, must be punished by God.

d) All this was a natural relationship in which Adam stood. Now to this natural relationship a covenant was added by God, which contained various positive elements.21

The distinction has its roots in the most ultimate objective nature (that is, the permanent essence of things), so that neither the subordinate objective “natures” or “states” of man, nor the subjective performances of man in such changeable states can change the permanent essence of things. Twentieth century Reformed theologians were increasingly less concerned about anthropology for the sake of anything outside of entrenched defenses of their soteriological distinctives. These are important, but they remain at the species level of nature and not the genus level. Belcher rightly remarks that this distinction is “logical and juridical, not temporal. Adam did not for a single moment exist outside of the covenant of works.”22

It should be noted that the section in the relevant section Westminster Confession begins with a statement that operates from this distinction:

The distance between God and the creature is so great that although reasonable creatures do owe obedience unto him as their Creator, yet they could never have any fruition of him as their blessedness and reward but by some voluntary condescension on God’s part, which he hath been pleased to express by way of covenant (VII.1)

Note the distinction between natural obligation and special fruition. It is the latter that is remedied by a second covenant, but notice that the former (natural obligation) is not eradicated by Adam’s failure in the first covenant. Man is still man—neither demon nor animal—and is thus duty-bound to offer up all that makes man a man, both unto God and toward his fellow man.

The Uniqueness of the Covenant

Another question for those who are serious students of covenant theology is the question of one covenant or two. There is a third covenant to talk about over and above the temporal plane, but we will come to that. The question of one or two is a distinct question because it treats covenant theology in its more proper “left to right,” or narrative, setting in history. Covenant theologians will use the words mono-covenantal versus bi-covenantal. We will revisit this in greater detail when we examine the view of Barth and his theological progeny. The idea is very simple, however. The question is whether the Bible itself presents to us one overarching covenant of God that swallows up everything from Genesis to Revelation, including the Garden of Eden all the way back to the first free act of God.

The first place many covenant theologians will turn in order to settle the distinct nature of a covenant is whether it is unilaterally imposed or entered into bilaterally—often the words “monopleuric” (one-sided) and “dipleuric” (two-sided) have been used for these. However, the category that tends to make the greatest difference is the way in which the unconditional elements as opposed to the conditional elements shape the covenant relationship.

This is such an important metric that the covenant of grace is considered by many to be utterly unconditional. Yet this can assume that the only purpose of the covenant of grace is to save its members from sin and death and this evil age. For our purposes, at this early stage of our study, it also tends to forget that even the first covenant assumed some kind of grace for it to be made in the first place.

It is quite true that the Hebrew word for “grace” or “favor” (חֵן) first appears in Genesis 6:8 and it is also true that grace has a special connotation throughout the Scriptures that presuppose sin. However, getting back to the notion of proper classification by genus and species, if one accepts that “unmerited” or “undeserved blessing” is an accurate general definition of grace, then one must conclude that Adam’s very first breath was a gift of God’s grace. While the redeemed sinner is doubly a recipient of grace, the creature, by virtue of his non-existent status prior to creation, is at least a once-recipient of grace. A nothing cannot deserve a some-thing.

This has important application to the matter of the basis of the reward Adam was to receive for obedience. Some are nervous of calling this a covenant of works on the ground that this implies merit.

Belcher’s remark is helpful here:

“God could have required obedience without any promised reward, and the covenant relationship does not place God in mankind’s debt. God condescends to mankind to enter into a covenant relationship out of grace, defined as the favor of freely bestowing all kinds of gifts and favors, temporal and eternal, on Adam in his condition after the fall.”23

Why then call it a “covenant of works” in ultimate distinction to the later “covenant of grace”? The simplest answer is the best to start with. When the Bible most clearly sets forth the gospel in contrasting terms—that is, when, in those clearest expositions in Paul’s letters, he holds before us the two basic ways of relating to God, the contrast is either between “grace” versus “works,” or else between “faith in Christ” versus “works of the law.”

There is something here that is the same as that covenant that God would later make with Israel through Moses at Mount Sinai; and yet there is also something that is not the same. Take what is similar first: “if a person does [the commandments], he shall live by them” (Lev. 18:5). Simply read the whole of Deuteronomy 28 and you will see this same arrangement for Israel at the threshold of the Promised Land—blessing for obedience, and the curse for disobedience.

But then notice what is different in those words, ‘for in the day that you eat of it’ (v. 17). Do you see that? It is a one-and-done. So the Confession says, “upon condition of perfect and personal obedience.” Not so with Israel.

From the days of Gibeah, you have sinned, O Israel; there they have continued … When I please, I will discipline them, and nations shall be gathered against them when they are bound up for their double iniquity (Hos. 10:9, 10).

Israel had sinned innumerable times each day, and year after year, and yet the judgment of God stretched itself like the bending back of a archer’s bow over time. With Adam, the path of disobedience should have been seen as an immediate abyss that would instantly open up. The arrow would strike all at once to inflict that mortal wound.

Before we examine this covenant in more detail, we should take a broader view in comparison between these two basic covenants of the Bible.

Witsius concisely offered two lists, that in which they agree and that in which they differ.

These covenants agree, 1st. That in both, the contracting parties are the same, God and man. 2dly. In both, the same promise of eternal life, consisting in the immediate fruition of God. 3dly. The condition of both is the same, viz. perfect obedience to the law. Nor would it have been worthy of God to admit man to a blessed communion with him, but in the way of unspotted holiness. 4thly. In both, the same end, the glory of the most unspotted goodness of God. But in the following particulars they differ. 1st. The character or relation of God and man, in the covenant of works, is different from what it is in the covenant of grace. In the former God treats as the supreme law-giver, and the chief good, rejoicing to make his innocent creature a partaker of his happiness. In the latter, as infinitely merciful, adjudging life to the elect sinner consistent with his wisdom and justice. 2dly. In the covenant of works there was no mediator: in that of grace, there is the mediator Christ Jesus. 3dly. In the covenant of works, the condition of perfect obedience was required, to be performed by man himself, who had consented to it. In that of grace, the same condition is proposed, as to be, or as already performed, by a mediator. And in this substitution of the person, consists the principal and essential difference of the covenants. 4thly. In the covenant of works, man is considered as working, and the reward to be given as of debt; and therefore man’s glorying is not excluded, but he may glory as a faithful servant may do upon the right discharge of his duty, and may claim the reward promised to his working. In the covenant of grace, man in himself ungodly is considered in the covenant, as believing; and eternal life is considered as the merit of the mediator, and as given to man out of free grace, which excludes all boasting, besides the glorying of the believing sinner in God, as his merciful Savior. 5thly. In the covenant of works, something is required of man as a condition, which performed entitles his to the reward. The covenant of grace, with respect to us, consists of the absolute promises of God, in which the mediator, the life to be obtained by him, the faith by which we may be made partakers of him, and of the benefits purchased by him, and the perseverance in that faith; in a word, the whole of salvation, and all the requisites to it, are absolutely promised. 6thly. The special end of the covenant of works, was the manifestation of the holiness, goodness, and justice of God, conspicuous in the most perfect law, most liberal promise, and in that recompense of reward, to be given to those, who seek him with their whole heart. The special end of the covenant of grace is the praise of the glory of his grace, Eph. i. 6. and the revelation of his unsearchable and manifold wisdom: which divine perfections shine forth with luster in the gift of a mediator, by whom the sinner is admitted to complete salvation, without any dishonor to the holiness, justice, and truth of God.24

We ought to end with one point that is common over all such places in Scripture. This regards are whole attitude toward the covenants. Witsius said,

It is not left to man to accept or reject at pleasure God’s covenant. Man is commanded to accept it, and to press after the attainment of the promises in the way pointed out by the covenant. Not to desire the promises, is to refuse the goodness of God. To reject the precepts is to refuse the sovereignty and holiness of God; and not to submit to the sanction, is to deny God’s justice.25

This was as true for Adam at the beginning as it is today, and vice versa.

_______________________

1. Cornelis P. Venema, Christ and Covenant Theology: Essays on Election, Republication, and the Covenants (Phillipsburg, NJ: Presbyterian & Reformed Publishing, 2017), 6.

2. cf. Karl Barth, Church Dogmatics (Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 1958), 3.1:231-32, 4.1:56-65.

3. Richard Belcher, “The Covenant of Works in the Old Testament,” in Covenant Theology, 63-64.

4. Belcher, “The Covenant of Works in the Old Testament,” in Covenant Theology, 64, 65, 66; italics mine.

5. Roberts, God’s Covenants, I:118.

6. Belcher, “The Covenant of Works in the Old Testament,” in Covenant Theology, 66.

7. Roberts, God’s Covenants, I:116.

8. Roberts, God’s Covenants, I:117.

9. Roberts, God’s Covenants, I:117.

10. Roberts, God’s Covenants, I:118.

11. Roberts, God’s Covenants, I:118.

12. Augustine, On the Literal Meaning of Genesis, VIII.4, 8.

13. William Perkins, Exposition of the Creed, quoted in Roberts, God’s Covenants, I:119.

14. Roberts, God’s Covenants, I:120.

15. Venema, Christ and Covenant Theology, 18.

16. John Murray, The Covenant of Grace: A Biblico-Theological Study (Phillipsburg, NJ: Presbyterian and Reformed, 1983), 5, 12.

17. Robertson, The Christ of the Covenants, 68.

18. Robertson, The Christ of the Covenants, 56.

19. Turretin, Institutes, I.8.3.4

20. Witsius, The Economy of the Covenants between God and Man, I:49

21. Geerhardus Vos, Reformed Dogmatics, Volume Two: Anthropology (Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, 2014), 31.

22. Belcher, “The Covenant of Works in the Old Testament,” in Covenant Theology, 68.

23. Belcher, “The Covenant of Works in the Old Testament,” in Covenant Theology, 69.

24. Witsius, The Economy of the Covenants between God and Man, I:49-50.

25. Witsius, The Economy of the Covenants between God and Man, I:47.