The Christian’s Subordinate Subordination

Be subject for the Lord’s sake to every human institution, whether it be to the emperor as supreme, or to governors as sent by him to punish those who do evil and to praise those who do good.

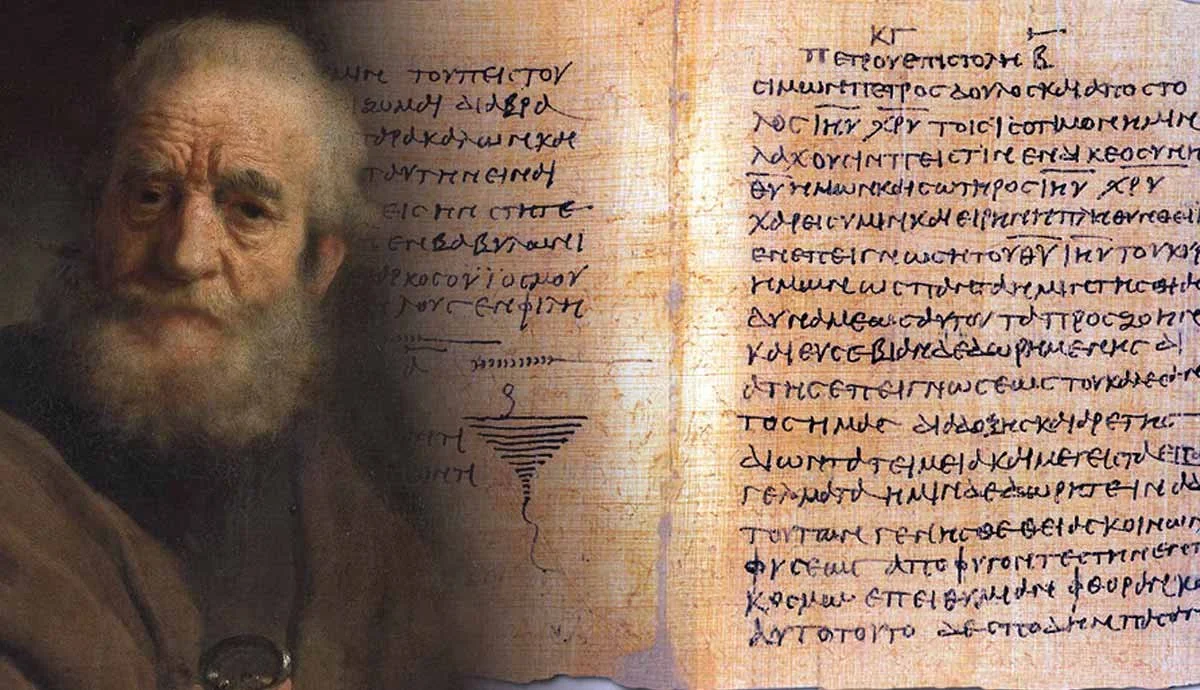

1 Peter 2:13-14

Notice that 2:13-14 belongs to a few larger units of logic. You could draw a few circles of unity in the themes here. But the one I want to draw your attention to is that theme of authority and submission; and the clue that there is a common idea that unites this theme is Peter’s expression here, ‘every human institution’ (v. 13b), so that when you get down to “servants” (2:18), and then “Likewise, wives” (3:1) and “Likewise, husbands” (3:7), and even way down to “Likewise, you who are younger, be subject to the elders” (5:5)—hopefully, in all of these cases, you will realize that these too are human institutions.1

In other words, civil government, labor, the home, and the church, are all species of the same genus that Peter is simply calling “human institutions.” There is an authority and submission design in every one of them. God is that Designer to each, and God’s glory is what is at stake in each. As Calvin said of this expression, “it is called a human ordination, not because it has been invented by man, but because a mode of living, well arranged and duly ordered, is peculiar to men.”2

Doctrine. The Christian is subordinate to all proper human authority—that is, all that has been instituted by God.

(i.) The are dilemmas in submitting to civil authority.

(ii.) There are historically diverse forms of civil authority.

(iii.) There is a twofold design to civil authority.

The are dilemmas in submitting to civil authority.

There are two dilemmas that Peter will help us resolve; and he is going to help us resolve this by giving us two qualifications.

On the surface, everyone knows what BE SUBJECT means. To be subordinate (ὑποτάσσω) is not only to obey, but to honor and discharge one’s duties toward some superior or officeholder, or maybe even, in the case of the whole institution, its rules or laws or customs. But in those same words comes the first qualifier: ‘Be subject for the Lord’s sake’ (v. 13a). What do I mean by a “qualifier” here? The expression “for the Lord’s sake” may seem to be only a modifier. In other words, Peter only gives us a motive for this subjection. Something about it will honor the Lord. But that actually is a qualifier as well. Let me start to build this concept with a few similar commands in other New Testament texts. Your job will be to tell if you start to see a pattern:

Wives, submit to your own husbands, as to the Lord (Eph. 5:22; cf. Col. 3:18).

Whatever you do, work heartily, as for the Lord and not for men (Col. 3:23).

Therefore render to Caesar the things that are Caesar’s, and to God the things that are God’s (Mat. 22:21).

In other words, obedience to a mere mortal is never, ever unqualified. Why? It is because our first dilemma here is vertical—Christ or Caesar? And that is not a dilemma between two equals. If Jesus said, “All authority in heaven and on earth has been given to me” (Mat. 28:18); and if Caesar represents some proper authority, then that some authority (Caesar’s) has to be inside of that all authority (Christ’s). All merely human authority, if it is proper authority, is a delegated authority from Christ. And that means that any proper submission to that authority is a subordinate subordination and not an ultimate subordination. So in the case of the Jerusalem authorities, which were both religious and civil, we read that,

they called [the Apostles] and charged them not to speak or teach at all in the name of Jesus. But Peter and John answered them, “Whether it is right in the sight of God to listen to you rather than to God, you must judge, for we cannot but speak of what we have seen and heard” (Acts 4:18-20).

Peter and John would have been ready to submit even to them—unless or until, those matters clearly revealed by God to be essential to the Christian faith and practice (that is, essential to either the gospel of Christ or the law of God) is trampled upon by the state. We are subordinate to mere mortals under that ultimate subordination.

Now comes a second qualifier that also might not seem like a qualification at first: ‘to every human institution’ (v. 13b). That is a universal application. How could it be a qualification? That is where our context at the beginning comes in. Every human institution included not only the civil government, but also the field of labor, home, and church. So EVERY becomes a qualification the moment you attempt to apply the universal application to only one case to the exclusion of the others. On what basis would you do that? There may be such a subordination of one institution to another, one authority to another, but it won’t come from this text. This text simply says to observe this toward every one of them.

So, with that second qualifier in mind, we can apply it to a second dilemma. Our first dilemma was vertical: Christ or Caesar. Our second dilemma is horizontal. This second dilemma can take on a few different forms, but it always boils down to one simple question: Which one? “Horizontally,” or down here among human institutions and human authorities, which one is properly ordered itself? Think of the very meaning of the word “sub-ordinate,” which implies an order under (sub). So there are these two dilemmas that we must think through to properly respond to Peter’s words here.

There are historically diverse forms of civil authority.

How does Peter describe the civil magistrate here? He gives us a glimpse into the Roman imperial form: ‘whether it be to the emperor as supreme, or to governors as sent by him’ (13c-14a). The Greek word Peter actually uses here is for king (βασιλεύς) a derivative of the similar word for kingdom (βασιλεία). The NIV and ESV use the word “emperor” presumably to help out the modern reader with the historical context. Indeed, in Rome this “monarch” or “one-head” was called the emperor; and, as the saying goes, When in Rome … But that raises our very question: Which readers of the Bible were in Rome? Roman Christians. And not only those in the church of Rome, but also all those in the first few centuries whose churches were planted across that empire. In fact, that second reference here, to the “governors” (ἡγεμών), is another unique feature of imperial Rome. Their territories were formed as military provinces and so their provincial governors existed to govern for Caesar.

I will have more to say about this in our application time, but as a basic principle: The Christian can only apply this to the real life circumstance by matching the imperative to the actual form of government we exist within, and not the first century Roman system.

There is a twofold design to civil authority.

The bulk of verse 14 has often been used to speak of the twofold purpose of the civil magistrate, namely: ‘to punish those who do evil and to praise those who do good.’ This does not sit very well with adherents to modern ideologies. One ideology sees government as a means to produce good that is not there, not to praise a good that has never been. That is Marxism. Another ideology sees government’s role limited to punish an evil that has already happened, on the ground of what is called the “Non-Aggression Principle.” It is this view that has taught us all to say: You can’t legislate morality! That is classical liberalism. So the notion that the governing agent exists both to punish evil and praise the good is counter-intuitive to our modern world.

What is meant by punishing evil? We must consult the rest of Scripture. God’s design in Genesis and His law moving forward from there give shape to the civil use of the law. To start with the easiest and first purpose of the civil magistrate, he must be an “avenger” with “the sword” as Paul teaches in Romans 13, first and foremost to protect the life of the image of God (Gen. 9:5-6). As Heinrich Bullinger said of the magistrate, that,

God commandeth to use authority and to kill, threatening to punish him most sharply, if he neglect to kill the men whom God commandeth to be killed. This sixth commandent of the law, therefore, doth flatly forbid upon private authority to kill any man.3

Psalm 82 is one classic text for how all civil magistrates will answer to God for their neglect in this justice. Life is the simplest element of the image of God to see this with. For the way that civil government exists to defend the liberty and property of persons requires more study; yet a government that cannot even observe that first principle of defending life is no government at all. A citizenry that does not have this foremost in its mind is not a moral people and lacks the intellect required to maintain its freedom and existence.

What is meant by praising the good? It means what it says. It does not mean changing hearts and producing spiritual good. Only God and the gospel can do that. Yet modern pietism is so keen to make this point that it ignores any other kind of good that God gives us to maintain. Paul says to even the Roman Christian: “Then do what is good, and you will receive his approval” (Rom. 13:3). If there is a wicked tyrant, then you will at least have God’s approval; but the design of the civil magistrate is that such a man possesses the character and the virtues fit for the office. This office exists—this man exists—for same ultimate end as any other. There is an “all who govern justly” (Prov. 8:16).

Turretin said of this,

The principle and supreme end of the civil magistrate as such …is the glory of God, the Creator, conservator of the human race, and the ruler of the world.4

Now I have a simple question. How can the civil authority punish evil and praise good if it does not know the difference between good and evil? To demand a civil magistrate who cannot speak to the difference between good and evil is as foolish as to demand a police officer who, when he looks down the barrel of his gun, cannot tell the difference between the mugger and the victim of a mugging. All such reasoning is fundamentally moral reasoning.

Practical Use of the Doctrine

Use 1. Instruction. Let us look at at least one exercise with our dilemmas. If it is the case that all authority belongs to Christ and that some of that same authority is delegated down to Caesar, then is it possible that Caesar would ever try to expand his circle? In other words, when Jesus says, “Render unto God’s what is God’s,” might Caesar command you to render unto Caesar some of what is God’s and not Caesar’s? Certainly. In fact, it happens all the time. What then?

We saw this play out in the different stances that certain Christian leaders had over the past 10 years. When one party is in office—Romans 13!—and when the other, “No Kings!” When a pandemic comes up, or mobs burst into churches, suddenly, the question over which magistrate we should obey if they conflict with each other because utterly arbitrary. Or did it? Invariably, the answer from those of a pietistic or progressive persuasion is that we ought to obey the officer (a) with the heavier artillery and (b) with disadvantage to the church. What we have very often is nothing more than a martyr-complex. Whatever power is most disadvantageous to the church and destructive to the individual rights of Christians must be what the Scriptures mean by proper authority. After all, “We lose down here” and “This world is not our home.” In fact, we begin to play God in the how and when of our persecution. This requires a deeper study. Our men’s ministry will be starting just such a study. In a few weeks, we will be reading a little book called The Lesser Magistrate Doctrine. I invite every man to join.

Use 2. Correction. About those several verses where the subordination of a worker, a wife, a church member, and even a child—that these are all qualified—no one typically has any problem with admitting that these authorities and the orders they give are not ultimate, that these are subordinate within an order where Christ alone is the Head. If a child’s teacher tells them to disobey a parent, or an employer pressures an employee to get by law enforcement, we recognize such dilemmas and we have intelligible reasons to work through them. Yet there is one exception, and one exception only. In the past few generations, in American Christianity, under the influence of pietism, Evangelicals have gotten the idea that the civil magistrate is the one exception. In this way, pietism breeds statism. The civil sphere is thought of as supreme, for if no other reason, because it threatens us with the most harm if we disobey. Thus we gage authority as animals who are moved by an utterly natural pecking order where might makes right. However, Peter’s “every institution” here offers no hierarchy, only a universal rule. This by itself gives us the action item to search out some criteria for how to navigate these dilemmas.

Use 3. Admonition. Many sermons about this text (as well as Romans 13:1-7, or even Titus 3:1-3) focus on the motive for submission. This is twofold, as Calvin summarizes:

for by refusing the yoke of government, they would have given to the Gentiles no small occasion for reproaching them. And, indeed, the Jews were especially hated and counted infamous for this reason, because they were regarded on account of their perverseness as ungovernable. And as the commotions which they raised up in the provinces, were causes of great calamities, so that every one of a quiet and peaceable disposition dreaded them as the plague, — this was the reason that induced Peter to speak so strongly on subjection. Besides, many thought the gospel was a proclamation of such liberty, that every one might deem himself as free from servitude.5

The motive, then, is to prevent Christ’s name from being dishonored. Wherever our conscience can allow, we must be model citizens. We must be the best of neighbors. We must not be known as malcontents. But the glory of God must be our universal motive that shapes our subordinate subordinations. If our situation is that we are utterly powerless, we tell the gospel by following Christ down a road marked by only suffering. But for the majority of Christians in the West, who still stand on ground once conquered by Christian influence, with the fabric of law, stretching back two millennia, and not yet extinguished: There is no virtue in laying down God’s law where we have never yet tried to follow it.

____________________________________________________________________

1. κτίσις can mean institution, ordinance, creation, or building.

2. Calvin, Commentaries, XXII.2.80

3. Bullinger, Decades, I:307.

4. Turretin, Institutes, III.18.34.5.

5. Calvin, Commentaries, XXII.2.80.