The Covenant of Redemption

It may seem to complicate things to introduce a third covenant after we had clearly seen that there are two main ones in the Bible. However, there must be some overarching explanation for how the covenant of grace does what it does. How is it that God begins again with one nation, Israel, and from one man, Abraham? Or, if there are any saved before Abraham, into what and on what terms are they saved? Besides, understanding how an eternal covenant relates to the covenant of grace is not too difficult.

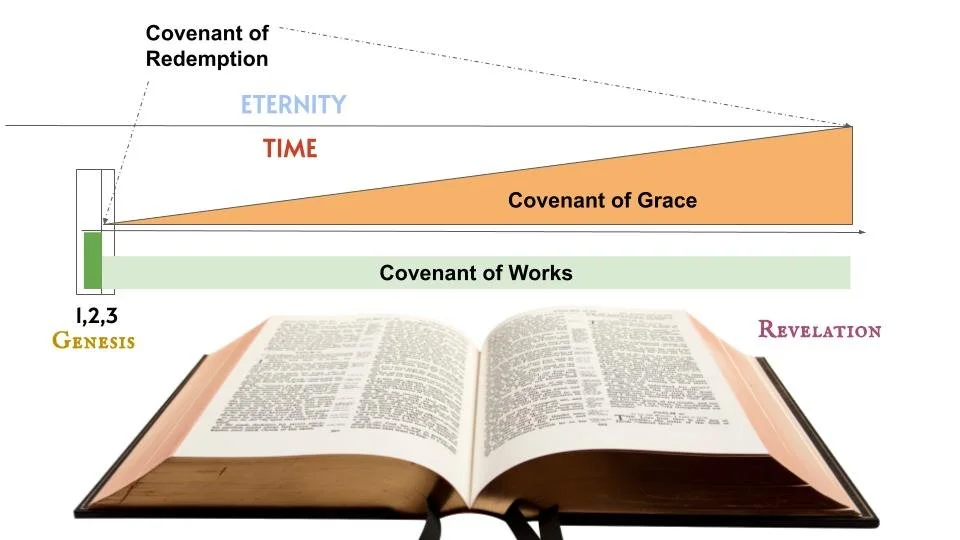

A simple picture will help. Imagine that the two main covenants already described are situated next to each other on the left-to-right timeline of biblical history—the covenant of works to the left, holding its place continuously for those who remain in Adam and not in Christ; and the covenant of grace emerging at the end of Genesis 3 in the most seed for, expanding to a clear announcement in Genesis 12 and occupying the majority of the biblical narrative for God’s people moving forward. A horizontal line just above divides heaven from earth, or, more to the point, eternity from time. It is in that eternity where the covenant of redemption is said to reside. But how so?

Guy Richard describes it concisely as “a pre temporal agreement between the persons of the Trinity to plan and carry out the redemption of the elect.”1

A fuller summary was given by the seventeenth century authors of a book entitled, The Summe of Saving Knowledge (1648), namely, David Dickson and James Durham:

The sum of the Covenant of Redemption is this, God having freely chosen unto life, a certain number of lost mankind, for the glory of his rich Grace did give them before the world began, unto God the Son appointed Redeemer, that upon condition he would humble himself so far as to assume the human nature of a soul and a body, unto personal union with his Divine Nature, and submit himself to the Law as surety for them, and satisfie Justice for them, by giving obedience in their name, even unto the suffering of the cursed death of the Cross, he should ransom and redeem them all from sin and death, and purchase unto them righteousness and eternal life, with all saving graces leading thereunto, to be effectually, by means of his own appointment, applied in due time to every one of them.2

Like covenant theology as a whole, this idea developed from the middle of the sixteenth to the middle of the seventeenth century. Calvin, Beza, Olevianus, Ames, and others, spoke in passing about some kind of an agreement between Father and Son before the ages began. The aforementioned David Dickson, Richard tells us, “was apparently the first to speak of it by name”3 in 1638. As one might expect, it was the generation of the Westminster Assembly that began to deploy the name and fuller idea. It has also sometimes been called the pactum salutis or “counsel of salvation,” or “counsel of peace,” after an expression from the Old Testament that we will observe.

This idea has come under fire for being exegetically thin, logically unnecessary to the justification of covenant theology, and perhaps even injurious to our doctrine of God. Why not simply leave it aside? Why not simply refuse to rule on it one way or the other?

Covenant of Redemption in Scripture

Richard offers a threefold classification of New Testament passages that only make sense if there was an agreement between Father and Son prior to the incarnation.

First, it regularly speaks of the salvation of the elect in terms of buying and selling (e.g., Acts 20:28; 1 Cor. 6:20; Eph. 1:7; 1 Pet. 1:18). But as Dickson points out, buying and selling presume that the parties have reached prior agreement regarding the terms of the deal. Second, the titles given to Jesus in the Bible indicate that the Father and the Son must have made some kind of prior agreement. Thus, the fact that Jesus is called our “propitiation” in Romans 3:25 and 1 John 2:2 is evidence that an agreement must have been reached beforehand in which the Son consented to give his life as a propitiatory sacrifice and the Father consented to accept it. Third, Jesus regularly speaks about his mission on earth in terms implying that he and the Father had made an agreement prior to his coming.4

One objection that might occur to anyone who recalls the criteria for the presence of a covenant in Scripture—namely, what attributes necessary for a covenant are present here? Gillespie argues that the most foundational attribute is here: agreement.5

Isaiah 42 is plainly a messianic prophecy. Like so much of Isaiah’s language of the Servant of the LORD, there is a typology in which Israel is the type and Christ the antitype. But the words that most concern us here are these:

I am the LORD; I have called you in righteousness; I will take you by the hand and keep you; I will give you as a covenant for the people, a light for the nations (v. 6).

That Christ will in some way “embody” the covenant at least implies that this was in view in eternity. The “I will give you” is rooted in “I have called you.”

Zechariah 6:13 is a central text. While Joshua the priest is the subject matter, the messianic type here works the same way as with those regarding David, or even Melchizedek, being both priest and king. This is further supported by the previous verse hinting at another Davidic-era name given to Jesus: “the man whose name is the Branch” (v. 12). Of this Joshua we are told,

It is he who shall build the temple of the LORD and shall bear royal honor, and shall sit and rule on his throne. And there shall be a priest on his throne, and the counsel of peace shall be between them both.

Assuming one accepts that this is ultimately about Christ, the focus then shifts to the expression “counsel of peace.” First, the plurality of parties must be considered, as Witsius does: “namely between the man, whose name is the Branch, and Jehovah: for, no other two occur here.”6

Psalm 2 is especially illuminating.

I will tell of the decree: The LORD said to me, “You are my Son; today I have begotten you. Ask of me, and I will make the nations your heritage, and the ends of the earth your possession (vv. 7-8).

Whatever the substance of this speech is, it is placed under the heading of divine decree. Richard cites an argument by Gillespie that the best Hebrew tradition for the root of the word used in this verse (חֹק) was understood to mean “to ordain, appoint, or covenant.”7 Moreover, Gillespie argued, the LXX renders this word πρόσταγμα, as in an “order” or “agreement.” At any rate, the eternal decree is here made compatible with divine speech—even, one might say, “inner-trinitarian speech.” Granting that this is also analogical speech for our benefit, it must still communicate truly what is something of an agreement that characterizes the decree. This brings us to our next level of difficulty.

One obvious New Testament text, and one to which Roberts and other seventeenth century theologians appealed, are Paul’s words in Galatians 3:16.

Now the promises were made to Abraham and to his offspring. It does not say, “And to offsprings,” referring to many, but referring to one, “And to your offspring,” who is Christ.

Since Paul’s context there is the relationship between Abraham and Moses—and therefore the promissory arrangement versus the one under law, it is easy to gloss over the significance of Paul’s words. It may even be suspected that Paul is being cryptic, saying nothing else about the sense in which Christ was the ultimate recipient of this promise. He does not speak about the when of Christ having received it; he goes right back to the when of the promise to Abraham versus the giving of the law.

Covenant of Redemption and Classical Theism

There are two basic ways to situate this covenant—one trinitarian and the other christological. Not that either ignores the relationship of the other, as if the trinitarian were insensitive to the redemptive-historical development, nor the christological unaware of squaring the relevant passages and expressions with God in Himself. It is more a matter of where to place the doctrine in one’s system. J. V. Fesko chronicles “that a majority of proponents of the doctrine adhere to the christological model.”8 The reasons in favor of that view have to do with (1) the preponderance of that focus in the majority of relevant texts, (2) the central—and nearly exclusive—focus on the Son as surety in the agreement, and (3) the Son’s identity as the chief party to the covenant as head of the elect. Some have insisted that the christological model risks becoming “sub-trinitarianism.”9 Others would not go that far, yet nonetheless remind us that such an “agreement” is more properly considered from the perspective of God’s eternal decree. Hence the trinitarian placement of the doctrine guards our theology proper. How does one express the parties in this model? Fesko writes, “So on the one side of the covenant is the Trinity, essentially considered. Christ, the God-man, is on the other side of the covenant.”10

What considerations lead people to infer that the covenant of redemption is unable to be reconciled to such a view of God in Himself? There are four basic difficulties:

(1) An implied experience of time and change.

(2) An implied eternal subordination in the Son.

(3) An implied division of the external works of the Trinity.

(4) An implied division of wills between the persons of the Trinity.

In order to answer the first, we simply need to recall the simple words of Psalm 2:7: I will tell of the decree. What is the covenant of redemption? It is theologians echoing this telling of that same decree.

Scott Swain explains,

The doctrine of the decree does not concern the beginning of God, because God has no beginning. The doctrine of the decree concerns the beginning of all things that exist outside of God. In more technical idiom: the divine decree is the internal work of the Triune God (opera Dei interna) that moves and directs the external works of the Triune God (operationes Dei externae). Thus understood, the divine decree functions as a hinge between theology’s two great themes: God and all things in relation to God.11

The conception articulated most famously by Thomas Aquinas, that in God there can be no potentiality and thus that the First Cause must be in pure act (actus purus) was seen by the Reformed orthodox as the most excellent way to reconcile God in Himself with all of the relational activity and properties apparently taken on by God for us. Hence, for someone as late as Herman Bavinck, “God wills himself and his creatures with one and the same simple act.”12

This begins to resolve both of the “division” difficulties—that of the external works of the Trinity and between the trinitarian persons. As Swain reviews, “while we may distinguish the objects of God’s will (i.e., God himself and God’s creatures), God’s will in itself is indivisible.”13 The Trinity was the “principle” of the decree, since the “decree” we are speaking of refers to God’s free will toward actual objects rather than to God’s natural, or necessary will, toward all logically possible and absolutely necessary objects.14

As to division of works considered within the missions of the Son and the Spirit, Fesko writes that, “The covenant of redemption is also the root of the Spirit’s role to anoint and equip the Son for His mission as surety and to apply His finished work to the elect.”15

Covenant of Redemption as the Ground of Grace in the Narrative

As suggested, the covenant of redemption is the eternal root or fountainhead of the covenant of grace; or, stated conversely, the covenant of grace is the narrative and progressive manifestation of the covenant of redemption in time.

This is the place to observe the unity of that covenant in time as well. Although we have not yet begun to define and describe the covenant of grace as it unfolds in Scripture, we should treat that here as a kind of “table of contents” that expresses the author’s outline prior to even arriving at the introductory view. It is a kind of “bird’s eye view” of the whole story or whole system.

Not that this must be an alternative to an eternal covenant, but if one wants to locate a preeminent promise to Christ in the biblical history, yet before that grace is extended even to Adam,

Roberts shows how this can be done in Genesis 3:15:

Here the woman’s seed collectively comprehends Christ and all his elect; the serpent’s seed, all the children of Satan. But to whom was this first promise made? Not to the serpent or Satan, for though it was immediately spoken to the serpent, yet it was directed to him as a threatening not as a promise. Not to Adam nor to his wife, for herein God directs not his speech to them at all, but only to the serpent; they are variously spoken to afterwards, as is clear to him that heedfully observes the text — and as yet they were incapable of the promise of grace, no course being taken as yet for satisfaction of divine justice for their sins, to whom then could this promise be made but unto Christ, and to his elect in him?16

This insight from Genesis 3:15, taken together with passages like Galatians 3:16, are what the Westminster divines had in mind in Larger Catechism Question 31,

Q. With whom was the covenant of grace made?

A. The covenant of grace was made with Christ as the second Adam, and in him with all the elect as his seed.

That brings up another passage that can be looked at, one which is cited as a proof text for that Catechism’s answer. These are the words of Isaiah 53:10, which say, “when his soul makes an offering for guilt, he shall see his offspring.”

Covenant of Redemption as the Ground of Grace in the Doctrine

Naturally this is the place to consider predestination. John 6:37 and Ephesians 1:3-14 are two passages that Reformed theologians have often appealed to in order to speak about predestination in the context of this eternal agreement. More recent Reformed theologians have had to do so partly to answer another objection from Barth and company. The argument was that Calvin had originally placed election in the context of Christ, where it belongs.17 Later scholastic Reformed theology had moved it to the doctrine of God and therefore conceived of God’s choice as a “bald” choice of individuals apart from Christ, and that this was then read into Romans 9.18

If the Barthians had more carefully read the tradition, they might have noted covenant theologians who spoke of such an eternal decree respecting a union with Christ in a diverse manner that accounts for both God’s view toward the union and the experiential union itself grafting us in by the Spirit. For example, the breakdown of Witsius was between a “union of the decree,” a “union of eternal consent,” and a “true and real union.”19 It was the first that considers election proper, the third that considers it in terms of the ordo salutis, but then the second considers it in terms of Christ as the chief party to the covenant.

While it is unsurprising that predestination features in this discussion, it may surprise the student of covenant theology to discover that justification comes up as well. How could this be, since justification is further down the field in that order of salvation? The question regards “the moment” of justification. This is already a bit of a misnomer, since an eternal act cannot be confined to “a moment” in any event. Nevertheless, we hear of the positions of John Gill on one extreme, insisting that justification must coincide with Christ’s act in eternity—namely His obedience being recognized by the Father. Thus, in reality we must be justified and pardoned “both together in the divine mind, and in the application of them to the conscience of a sinner.”20 Some Reformed theologians have attempted to make this same division under the labels active justification and passive justification—the former being “God’s imputing Christ’s righteousness to the elect in the pactum salutis”; the latter being the experiential realization “of Christ’s righteousness by faith.”21 One brand or another of this division was Turretin, Witsius, Bavinck, and Vos.

On the other extreme we are said to find the position of Jonathan Edwards, because he spoke of justifying faith also in terms of a persevering faith. I am still unwilling to dismiss the jury on what Edwards actually held to. Some statements are taken from his Miscellanies, written quite early. The better source is his book on Justification by Faith Alone (1734) in which he clarifies that the role of persevering faith is what he calls a “natural congruity”22 with having a saving interest in Christ, so that such persevering faith is “virtually contained in that first act of faith.”23 But he is clear that “a sinner is actually and finally justified as soon as he has performed one act of faith.”24 Whether Edwards held to the view of so-called “final justification” or not, the important point for us is that the eternal act of justification alone and the final discovery of justification in the end—these are positions outside of the mainstream of Reformed covenant theology.

As with the covenant of works, so with the covenant of redemption, Barthians and other modern theologians have detected the static, the abstract, the impersonal. It has been said that the covenant theologians employed mercantilist language here in such a pact. To the contrary, it was inter-trinitarian love that was always in view. So in the prophet, Israel is told,

I have loved you with an everlasting love; therefore I have continued my faithfulness to you (Jer. 31:3).

The last and most important thing to be said about why the covenant of redemption matters as a grounding concept for the covenant of grace (or life as Roberts calls it) is that the ultimate Party is of ultimate importance. Christ must be exalted at the beginning of one’s treatment of the second covenant, and one cannot get there simply by moving left to right in the text. Here, a covenant theology that is true to the Bible teaching, must move back and forth in the Bible’s narrative. In Roberts’ Aphorism 1, he quickly brings this out: “One Scripture testifies that Jesus Christ is the last Adam.” He then cites 1 Corinthians 15:45-47, and so the claim is that one has to account for the truth of 1 Corinthians 15:45-47 in the movement from Adam to Abraham. Or, to state it another way—another Man has to be factored in in our movement from Adam to Abraham, and neither Adam nor Abraham will qualify to be that man. Nor will any other mere mortal in between Adam and Abraham. So what does Paul say that is so important there?

Thus it is written, “The first man Adam became a living being”; the last Adam became a life-giving spirit. But it is not the spiritual that is first but the natural, and then the spiritual. The first man was from the earth, a man of dust; the second man is from heaven.

Roberts continues, “Here are two Adams opposite one to the other, and the Lord Christ is the second or last of these two Adams.”25 In short, such a covenant must be made with man (adam), yet only the perfect Man can fulfill the terms. Everything about Him must be greater.

____________________________________________________________

1. Guy M. Richard, “The Covenant of Redemption,” in Covenant Theology, 43.

2. David Dickson and James Durham, Summe of Saving Knowledge, 2.2, quoted in Richard, “The Covenant of Redemption,” in Covenant Theology, 47.

3. Richard, “The Covenant of Redemption,” in Covenant Theology, 44.

4. Richard, “The Covenant of Redemption,” in Covenant Theology, 46, italics mine.

5. Gillespie, Ark of the Covenant Opened, 6, quoted in Richard, “The Covenant of Redemption,” in Covenant Theology, 46.

6. Witsius, The Economy of the Covenants Between God and Man, I.2.2.7 [167].

7. Gillespie, Ark of the Covenant Opened, 11-12, quoted in Richard, “The Covenant of Redemption,” in Covenant Theology, 48.

8. J. V. Fesko, The Trinity and the Covenant of Redemption (Ross-shire, UK: Christian Focus Publications, 2016), 15.

9. cf. Robert Letham, “John Owen’s Doctrine of the Trinity in its Catholic Context,” in The Ashgate Research Companion to John Owen’s Theology, ed. Kelly M. Kapic and Mark Jones (Surrey: Ashgate, 2012), 196.

10. Fesko, The Trinity and the Covenant of Redemption, 17.

11. Scott R. Swain, “Covenant of Redemption,” in Christian Dogmatics: Reformed Theology for the Church Catholic, ed. Michael Allen and Swain (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2016), 107.

12. Herman Bavinck, Reformed Dogmatics, II:233.

13. Swain, “Covenant of Redemption,” 114.

14. cf. Francis Turretin, Institutes of Elenctic Theology, I.3.13.1.

15. Fesko, The Trinity and the Covenant of Redemption, 132.

16. Roberts, God’s Covenants, I:209-10.

17. Barth, Church Dogmatics, II/2:54, 140, 158.

18. Barth, Epistle to the Romans (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1968), 347.

19. Witsius, Conciliatory or Irenical Animadversions on the Controversies Agitated in Britain, Under the Unhappy Names of Antinomians and Neonomians, VI.ii-iv.

20. John Gill, A Complete Body of Doctrinal and Practical Divinity, Volume 2 (Choteau, MT: Old Paths Gospel Press), 228.

21. Fesko, The Trinity and the Covenant of Redemption, 31.

22. Jonathan Edwards, Justification by Faith Alone (Orlando: Soli Deo Gloria Publications, 2000), 88.

23. Edwards, Justification by Faith Alone, 90.

24. Edwards, Justification by Faith Alone, 88.

25. Roberts, God’s Covenants, I:186.