The Most Precious Thing on Earth to God

knowing that you were ransomed from the futile ways inherited from your forefathers, not with perishable things such as silver or gold, but with the precious blood of Christ, like that of a lamb without blemish or spot.

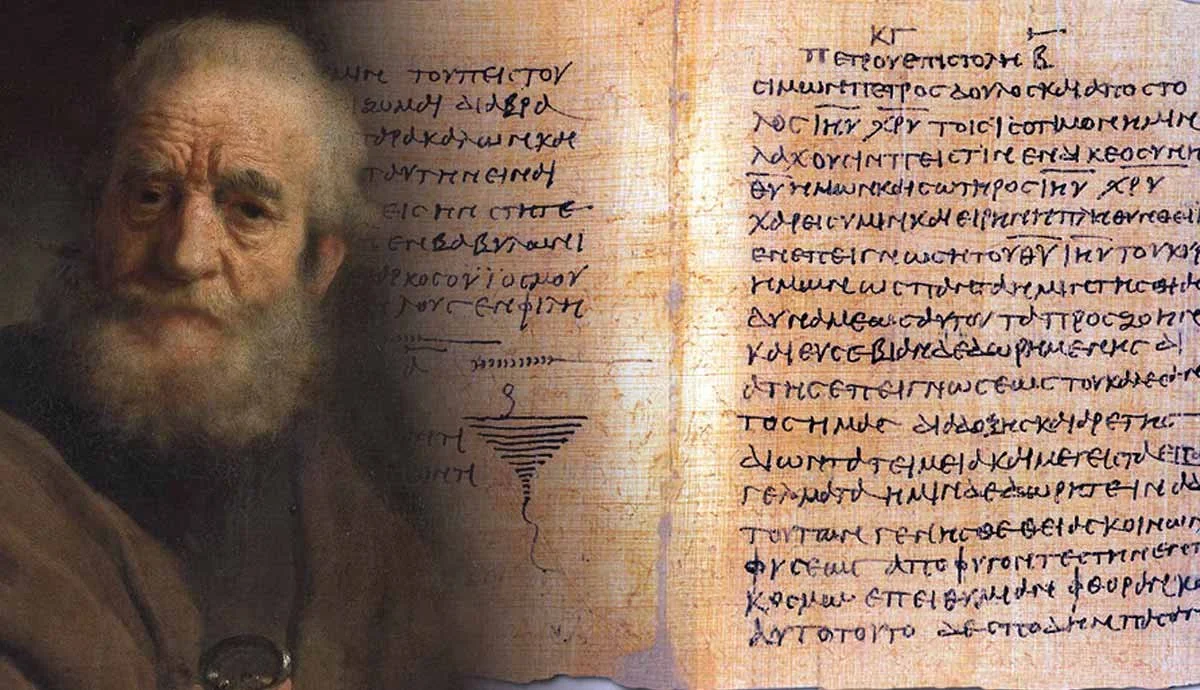

1 Peter 1:18-19

The question of Peter’s exact audience can really come to the forefront here. I want to suggest that it doesn’t matter whether he has primarily Jews in his audience with some Gentiles coming in as newcomers, or whether it is already predominately Gentiles and they are being spoken to in the same way that Paul seamlessly brings his Gentiles audiences into the ancient Jewish story (cf. Rom. 14:1-15:7; 1 Cor. 10:1-22; Eph. 2:11-20). Whether these ‘futile ways inherited from your forefathers’ (v. 18b) allude to the literal blood of the old covenant sacrifices, or whether the reference to other ‘perishable things such as silver or gold’ (v. 18c) makes the same point to the Gentiles’ ancient religions, the lesson remains the same.

What is that lesson? If you are hoping to raise up to God any precious commodity from the dust of this earth as if it will pay back to Him what we have stolen and trampled upon, all of that is futile. But there is good news. There is one thing that is not futile and in fact is infinitely precious to God.

Doctrine. The most precious thing on earth to God is the blood of Jesus—and therefore the believer is made precious to God.

(i.) The Past Tense of this Ransom

(ii.) The Human Alternatives to this Ransom

(iii.) The Divine Valuation of this Ransom

The Past Tense of this Ransom

Before we get to the tense in particular, we must examine the word: ἐλυτρώθητε is from the root λυω which means “I loose” or “I set free.” This is why various English translations use either the word “ransom” or “redeem.” When they are considered together, the ransom is the price of the transaction, whereas the word redemption would more properly refer to the transaction itself. The reason why the rendering “ransom” makes sense here is that Peter’s analogy of the precious commodities to the blood itself has the payment proper in view rather than the transaction as a whole.

Now that word is in the aorist passive—passive because it is happening to you. No slave ever purchased himself off of the auction block; aorist because it is a past action that was entered. So Peter speaks of a thing accomplished: ‘knowing that you were ransomed’ (v. 18a).

If we put these two concepts together—what it is and when it was—we get a past purchase of us by Christ. As Paul said, “In him we have redemption through his blood” (Eph. 1:7). Those two little words—WE and HAVE—signify a particular people (We) and an actual redemption secured (Have). “It is finished” (Jn. 19:30). When we sing that Jesus Paid It All, we mean that He paid for every single sin: past, present, and future, so that no sin could ever become un-atoned for, no amount of the satisfaction of God’s justice could ever fall out of His account. No un-ransom. When we sing in the hymn, Man of Sorrows, the line, “Full atonement, can it be! Hallelujah, What a Savior!” we hopefully mean to worship the Lamb who will be worshiped in heaven for the same: “by your blood you ransomed people for God” (Rev. 5:9). The ransom is all there; the redemption has been accomplished.

It is not simply that the blood of Jesus is powerful enough—fully sufficient for the sins of as many people as possible—but that an actual people group have been marked out for purchase. There is an “All that the Father gives to me” (Jn. 6:37), or as Peter opened off this letter with, to those who are “elect … for sprinkling with his blood” (1 Pet. 1:1, 2). The author of Hebrews puts it in two different expressions, “that those who are called may receive the promised eternal inheritance, since a death has occurred that redeems them from the transgressions committed under the first covenant” (Heb. 9:15). Or a chapter later: “For by a single offering he has perfected for all time those who are being sanctified” (Heb. 10:14). This ransom secures an actual, full, and particular redemption.

The Human Alternatives to this Ransom

How could there ever be an alternative for someone who knows what we have just heard? And yet one of the chief things all Christians have been ransomed from is something Peter calls ‘futile ways inherited from your forefathers’ (v. 18b). I said that the analogy to precious metals suggest that this is a bigger principle than can be reduced to only the old covenant system of ancient Israel. Three times in Ephesians 1, Paul ends his treatment of what the Father does in salvation, and then what the Son does, and then what the Spirit does, with a refrain of worship—namely, “to the praise of his glorious grace” (v. 6; cf. 12, 14). Here is another place that teaches the same truth. Jesus atoned for all your sins so that you would credit Him for the totality of that atonement. He did not shed His blood for you to pretend that you contributed anything other than the sin He had to pay for. You have been ransomed from not only from alternative practices, but, for that very reason, you have been ransomed from false doctrines of Christ’s work. False ideas of this ransom are futile doctrines—ideas that will vex your mind, water down your gospel, assault your conscience, and waste your life!

But in what sense could these be ‘futile ways’ to the Jews, since what they had inherited was God’s own law? The answer here is no different than how we parse the words of Jesus in the Sermon on the Mount—since He was not setting aside the actual law of Moses, but rather what He called “the tradition of men” (Mk. 7:8). So with respect to the whole of the old covenant, “God has done what the law, weakened by the flesh, could not do” (Rom. 8:3), or elsewhere, “the Scripture imprisoned everything under sin” (Gal. 3:22). So the spirit of the law was never futile, for what it was intended to do, it did; but the sinful flesh of man was futile to do what the law required. That is why when the gospel was preached to the Jews of the first century, it came in this form: “by [Jesus] everyone who believes is freed from everything from which you could not be freed by the law of Moses” (Acts 13:39). The physical children of Israel in the first century, whom God elected to come to faith in Jesus—these were ransomed by Christ’s blood from the futility of their own flesh, from the reflection of human effort in the mirror that they had made of the law.

The Divine Valuation of this Ransom

The adjective here (τίμιος) has a dominant New Testament use to describe what we might call “precious commodities”—especially “precious stones” (1 Cor. 3:12; Rev. 17:4; 18:12, 16; 21:11, 19)—though even when it describes other things, they tend to be the spiritual things of God in terms of honor and respect and being dear: Paul’s very life (Acts 20:24), marriage (Heb. 13:4), and God’s promises (2 Pet. 1:4). And even when the farmer’s everyday fruit is called “precious” (Jas. 5:7), it is in order to show how much more precious the fruit of the Spirit ought to be regarded in our lives. So what are we being told here? God values, above all, the blood of His own Son.

[Christ] gave himself up for us, a fragrant offering and sacrifice to God (Eph. 5:2).

The blood of Jesus appeased God. It both satisfied God’s just wrath and reflected to us the divine approval in the Son. In one of the classics I will have my students read next semester, Anselm answers the question Why God Became Man (Cur Dues Homo?); and he faces the difficulty that it does not seem fitting “that God allows [His Son] to be treated in this way, even if it is with his consent.” He replies,

On the contrary, it is most fitting that such a Father should agree with such a Son, if he has a desire which is praiseworthy in being conducive to the honor of God and useful in being aimed at the salvation of mankind, something which could not come about in any other way.1

So we have divine delight in the Son’s honor and the appeasement of divine wrath in one receiving of the ransom.

Peter gives us the ground of this valuation. He gives it through a familiar analogy: ‘like that of a lamb without blemish or spot’ (v. 19b). If “it is impossible for the blood of bulls and goats to take away sins” (Heb. 10:4), then it is not clear how lambs could do any better. There is nothing intrinsic to the literal animal called a lamb that is morally pure. The clue to the analogy is in the stipulation about blemishes and spots.

If his offering is a burnt offering from the herd, he shall offer a male without blemish (Lev. 1:3).

But if it has any blemish, if it is lame or blind or has any serious blemish whatever, you shall not sacrifice it to the LORD your God (Deut. 15:21)

Recall the Lord’s indictment of the priests, “When you offer blind animals in sacrifice, is that not evil? And when you offer those that are lame or sick, is that not evil?” (Mal. 1:8).

So one of the crucial attributes of Christ’s person—sinless—plays a role here in being a perfect sacrifice. As the author of Hebrews completes the thought:

how much more will the blood of Christ, who through the eternal Spirit offered himself without blemish to God, purify our conscience from dead works to serve the living God (Heb. 9:14).

A pure conscience, for one that has been impure, can only come from one who is intrinsically pure. And it is this that God values when He values the blood of His Son.

Practical Use of the Doctrine

How do these words about our ransom function in the larger statement by Peter? It is the one we began in the past few verses about our practical walk. The word ‘knowing’ (v. 18a) here is the connection. The ransom is the ground of our walking in holiness and conducting ourselves in fear throughout our exile. How so?

Use 1. Admonition. Many attempt to pay back God. Even many genuine believers who will confess with sincerity the doctrine of justification by faith alone and the finished work of Christ alone as their way of acceptance to God—even here, we forget, we neglect, and we are assaulted by the devil and our own conscience. And so we fall back into making ourselves debtors, perhaps, we think, even good enough debtors. But what does Paul say?

Now to the one who works, his wages are not counted as a gift but as his due. And to the one who does not work but believes in him who justifies the ungodly, his faith is counted as righteousness (Rom. 4:4-5).

Not only is coming to God as one who has exchanged satisfactory labor dishonoring to Him. Exchange from any other commodity is impossible anyway.

Truly no man can ransom another, or give to God the price of his life, for the ransom of their life is costly and can never suffice, that he should live on forever and never see the pit (Ps. 49:7-9).

Let us not give ultimate offense to God by measuring our merits up to those of His Son, especially when His was His very life blood. If Peter’s ground of walking in holiness and the fear of God is a growing knowledge of such a ransom, then it makes sense that to reject this truth is opposed to the fear of God.

Use 2. Consolation. What we are freely given cost Jesus what is most precious. God so values what is spiritually united to the content of that cup we are about to drink from, that it is unthinkable that the blood of Jesus could ever lose its power. Its value to you as you drink from it, is God’s valuation of it. Do not think that there is a power in your sin that weighs more to God than the preciousness of His Son’s blood. Do not see in the reflection of that cup your sins having the last word, when, in fact, Christ’s blood has the last word—“It is finished” He says, and Paul exclaims, “Who shall bring any charge against God’s elect?” (Rom. 8:33). Do you see what such a charge against you would amount to? That God should consider such sin to weigh more on His scales of justice than the precious blood of His Son.

The jealousy of God over that which He has claimed is good news for the believing soul. Since the most precious thing on earth to God is the blood of Jesus—therefore the believer is made most precious to God now.

________________________________________

1. Anselm, Cur Deus Homo? in The Major Works (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998), 10 [281].