What is the Trinity?

What is meant by “Trinity”?

By “Trinity” we mean one divine essence, three divine persons. This is what distinguishes the Christian idea of God from the other two monotheistic religions, Judaism and Islam. Even in the Old Testament, for the ancient Jews, while there were a collection of texts that bear witness to the triune nature of God, it is not until the New Testament that one can see the fullness of its revelation.

Questions 5 and 6 of the Westminster Shorter Catechism give us the simplest view into the two main truths that have to be put together:

Q. 5. Are there more Gods than one?

A. There is but one only, the living and true God.Q. 6. How many persons are there in the godhead?

A. There are three persons in the Godhead; the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost; and these three are one God, the same in substance, equal in power and glory.

Christian theologians have always been well aware that the word “Trinity” is not in the Bible. This is not a problem. Theology is done on the concept level. It is not the mere tracing out of verbal signs as an end in themselves. We might pause to consider that other words such as “monotheism” or “impute” or “biblical,” or “eternal state,” or any other number of terms that are suitable synonyms for ideas that all would agree are taught in the Scriptures, are not “in the Bible.”

Scripture and the Trinity

The doctrine of the Trinity has rightly been described as “progressively revealed” in the Bible. While the Old Testament does give us allusions of its truth, the relevant texts must be treated as pieces of a much larger puzzle, and as making sense mainly within the context of God’s promises to his covenant people. Without that appreciation for a building redemptive history, the majority of Old Testament texts will come across as random and forced. Having said that, we can consider three classes of texts that give different kinds of evidence.

Naturally, Genesis 1:26, 3:22, and 11:7 are cited as instances of 1. a divine speaker 2. addressing the divine. That is to say, not only are words like “us” used, but attributes and actions are spoken of concerning the personal object of the personal subject’s speech which cannot be true of any being less than God. This is our first class of texts, those of first-person plural and second-person divine discourse. The same phenomenon is witnessed in Isaiah 6:8, “Then I heard the voice of the Lord, saying, "Whom shall I send, and who will go for us?" While Isaiah 54:5 is not inter-trinitarian speech, the word "Maker" is plural in Hebrew.

A second class of texts are those mysterious visitations, or appearances, from angels (angelophanies), most of which can also be shown to be a kind of “appearance” of Christ (Christophany) or more generally of God (theophany). Such texts include Genesis 12:7; 16:7-14; 18:1; 32:24, 28; Exodus 24:9-11; 33:11; Numbers 12:8; Deuteronomy 31:14-15; 34:1; Joshua 5:13-15; Judges 6:6-24; Isaiah 6:1-6; and Daniel 3:25. Which specific class each of these fit within is a subject that is not as simple to resolve as it may appear at first glance. Books II and III of Augustine’s classic On the Trinity is perhaps the most masterful treatment of this subject in church history, and by itself worth the price of the book.

There is one last class of texts that round out our signs to the Trinity in the Old Testament. However, these are the passages that must be worked out in terms that theologians call “the economy of grace,” or in other words, that progressing history of redemption where God sends his Son, and then both Father and Son send the Spirit. The obvious problem in proposing this to a Jew is that we are relying on much New Testament “background” that is really foreground. That is a legitimate method of interpretation if what we are doing is mere theology or else preaching. It is not a helpful approach in apologetics. Having said that, Isaiah 43:10, Psalm 2:7, 110:1, and Micah 5:2 are passages of note in this class. If we ask for one verse where all three Persons are featured, the prophet Isaiah delivers: “And now the Lord God has sent me, and his Spirit” (48:16). Here it is the Son who speaks, but he speaks through the prophet.

All of this to arrive at the New Testament. There is a reason that the triune nature of God would be revealed more fully and all of a sudden here.

This is the Incarnation of Christ and the outpouring the Spirit. And this is no mere addition of two actors onto the stage. We must consider what the Son and the Spirit do in salvation. With Christ, we have God with us—the Word made flesh (Jn. 1:14). With the Spirit, we have a renewed heart and with it an illumination of the deep things of God (1 Cor. 2:11-13).

Fred Sanders distinguishes between two basic ways to demonstrate the doctrine of the Trinity. The first we are hinting at here. That involves “entering more thoroughly into the meaning of Scripture.” Here the Trinitarian persons turn out to be everywhere because with new eyes we see what the Father, Son, and Spirit do. The second way is what Sanders calls a “piecemeal proof” where you “announce in advance the basic elements of the doctrine and then prove each of the various elements seriatim” [1].

There are the familiar New Testament passages to which we commonly appeal: Matthew 28:19-20; John 1:1-3, 18, 10:30; Acts 5:4, 9; 2 Corinthians 13:14; Ephesians 1:3-14, and 4:4-6. But given the logic of the doctrine, we must also include all of the texts that show the deity of either the Son or the Holy Spirit, and all of the texts that show subject-object distinction between the three Persons.

But how can all three Persons be one God, and each be different from each other?

In speaking of the Trinity, whether in Scriptural or later doctrinal formulations, there is a distinction to be made between 1. what is equal in the divine essence; and 2. what is proper to each of the three divine persons.

Logic and the Trinity

When people raise the objection that the Trinity involves a logical contradiction, it becomes quickly evident that they misunderstand either the nature of logic or what the doctrine is claiming, or perhaps both.

Cumulatively the Bible teaches that: (1) There is but one God; (2) All three of the Persons are referred to as God; (3) There is subject-object distinction between the Persons. If all three of these premises are sound, then the conclusion of One God in three Persons necessarily follows.

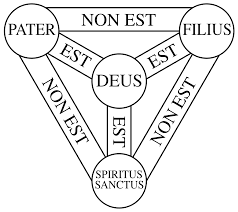

Now, in order for any two or more terms to contradict (by the law of noncontradiction), we would need to show a genuine A and ~A. So, for instance, if the Trinity was “one gods and three gods” or “one person and three persons,” in either of those cases, we would have a real contradiction. However, this is a case of “one what, three who’s.” One God, three Persons.

Church History and the Trinity

It will often be asked: When was this doctrine invented? The doctrine of the Trinity began the moment that its truth was revealed. Contrary to popular belief, while we may speak of doctrine as a product of church reflection, the truth of a doctrine is not reducible to a church “product.” A doctrine is either true or false, and the criteria for whether it is one or the other must be found on other grounds. The moment there is belief about any particular thing, there is a doctrine of that thing.

But was it not codified by Councils? It was certainly more codified at Nicea (325) and Constantinople (381), but the ways it was articulated were already being expressed by church fathers from the second century, and of course the relevant biblical passages constitute its doctrine.

The reason that there were such councils is not because of any fundamentally new idea. Rather, the church had to respond to a few errors about the nature of God that are still with us. Those ideas can be roughly divided into three. At one extreme one can attempt to protect the unity of God at the expense of the revealed persons. Hence Modalism does this by explaining the persons as mere “modes” in which God’s existence has been manifested in time. He was the Father in the Old Testament, the Son during the incarnation, and the Holy Spirit starting at Pentecost. On the other extreme, one can press the three persons over against the one essence, making them three divine entities, or three essences, which we call Tritheism.

Attempts were made to mediate between these. Arianism exalted the oneness of God, so that the Son was conceived of “similar substance” (homoiousios) to the Father, rather than the “same substance” (homoousios). As Arius was reputed to have said about the Son, “There was when he was not.” Adoptionism held that the Son became divine by virtue of being made the Son of God at his baptism, which was the first point in the temporal narrative that this was said about Jesus.

None of these positions did justice to all that the Scriptures taught. None of these could explain why Christ and the Holy Spirit were to be worshiped, and how the Persons could refer to each other as having what is proper to distinct persons.

Is the Trinity an essential doctrine?

Think of it this way — If we take away our knowledge of the Trinity, then the biblical worldview would collapse and there would be no gospel. In other words, objectively speaking, the Trinity is absolutely essential to the Christian faith.

Things get one notch trickier when viewing this from a subjective point of view. In other words, supposing we ask it this way: Is belief in the Trinity essential to one’s own salvation? The answer is that it depends on what is meant by “belief.” If we are talking about a profound understanding of the mystery of the Trinity, well, then no, for that would be to make our intellectual performance a kind of meritorious work. And besides, no Christian has accomplished more than scratching the surface of its mystery.

On the other hand, if what we are talking about is someone who sees what the doctrine means and turns away in disgust or pride, then this is entirely another matter. And this is the position that one who calls themselves a Unitarian or a Modalist has really put themselves in. These are not simple Christians who are making their first attempts to express what they see in Scripture. These are those who say, “We see,” and thus their error is also sin.

Resources for Further Study

In our own day, several excellent books have been written on the doctrine of the Trinity. These can get one into the deep end of the pool very quickly, but there is no avoiding that. The subject matter is unavoidably infinite. That being the case, one should start with the works by Reeves and the first title by Sanders.

Robert Letham, The Holy Trinity

Michael Reeves, Delighting in the Trinity*

Fred Sanders, The Deep Things of God*

Fred Sanders, The Triune God

Fred Sanders & Scott Swain, ed., Retrieving Eternal Generation

Scott Swain, The Trinity

Or, one can go back to the classic of Augustine, On the Trinity.

________________________

1. Fred Sanders, The Triune God (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2016), 172.