The Hypostatic Union: Four Crucial Questions

There came a time when confessing Nicene orthodoxy was not enough. Arianism had survived among barbarian converts up north, and was by no means extinguished even among the courts of the eastern Empire. But as an official church doctrine, most confessed that Christ was “God of God, Light of Light, very God of very God; begotten, not made, being of one substance with the Father, by whom all things were made.” New errors would emerge in the first half of the fifth century.

How is the union itself, between divine and human, to be understood in the incarnation? We know the name of this resolution in historical theology as the Hypostatic Union. There is, however, a difference between knowing a term and even roughly the object to which it applies, as opposed to understanding the concept in an intelligible way. The word “hypostatic” comes from the Greek hypostasis. Here we have another term from the ancient languages that would join homoousios and consubstantia, as those utilized by the architects of those creeds in order to attain maximal clarity.

The etymology of the word is a construction of the preposition which can mean “under” (ὑπό) and “standing” or “state of existence” (στάσις). The most wooden literal product of hypostatis, then, would be a “standing under,” or, in other words, “underlying” something.

Why, then, did those in the East especially use this word to mean “person” as in each person of the Trinity? One frequent observation among historians of theology is that the two “sides,” whether conceived as East and West, or as Greek and Latin, were speaking past each other, an unhappy predicament that the best theologians eventually discerned and factored into their reflection.

It may be that this division in Christology, as is often the case in theology, resulted from a division over theological method. In this case, it was even exacerbated by two different approaches to the Scripture. The school in Antioch was known for its literal reading of the text, whereas the Alexandrian school excelled in allegory. One of the implications of this is that the former would tend to view Jesus in an inductive manner, working with the bulk of its data as the Gospels present Him moving through the narrative of time and relating to other human beings. The latter would tend to begin with more abstract appeals to necessary truths in order to explain this or that about the what and the why of the incarnation.

A Syrian monk named Nestorius would rise to prominence, from Antioch to becoming the archbishop of Constantinople. He would quickly make a political stench of himself in his quest for doctrinal and moral purity. When his theology was set forth by opponents, a controversy as heated as that leading up to Nicaea emerged. Nestorius warned of those who made “the indiscriminate ascription of both divine and human attributes and characteristics to the one person.”

The main antagonist he had in mind was Cyril of Alexandria, who would write a little book On the Unity of Christ. By that title, one would rightly expect a great stress put upon the union in the Person. Since Cyril died in 444, one Eutyches had taken his doctrine to an extreme, which it is why the position is alternatively called Eutychianism.

The notion that Christ was a whole human person distinct from the divine Son is the heresy known as Nestorianism. It was initially known as the Antiochene or Syrian doctrine of “the Two Sons.”1 Whether Nestorius actually held to the view that is attached to his name is immaterial for the purposes of systematic theology.2 What matters is how it played a role in the formulation of the Chalcedonian Creed of 451 and of what exactly its rationale and its error consists. The opposite extreme, namely, that the incarnation involved an amalgamation of two originally distinct natures—divine and human—and became one (mono) nature (physis) is the heresy named monophysitism.

The Council of Ephesus in 431 had already condemned Nestorius. There Cyril presided, and it was strategic that the city in which it was proclaimed “Great is Artemis of the Ephesians!” (Acts 19:28) would serve as a fortress of sentiment for Mary as the “bearer of God” (theotokos), where Nestorius at least suggested the more modest “bearer of Christ” (Christokos). Antioch would form its own council in response and there they condemned Cyril. For all of this, the emperor initially deposed them both.

In 451, Emperor Marcian and Empress Pulcheria, would officially convene the Council of Chalcedon to resolve the dispute. This would be a larger event than Nicaea, since over five-hundred bishops would attend. Interestingly, there were twenty-eight “disciplinary canons” that touched on matters of authority, and neither Rome nor Constantinople are treated as heads over other bishops. The deliberations at Chalcedon would lead to further schism, as a Nestorian church would extend itself eastward, even into China. Others would be known as Miaphysites, essentially taking a more positive view toward the doctrine of Euthyches and regarding the rest of Christendom as “Chalcedonians.”

What matters most about Chalcedon is its statement of the truth about Christ that it produced: the Chalcedonian Definition. The questions of theologians go beyond mere history. We want to know the truth. We do not turn back at what turned others away, or in different directions. We want to know, as far as God has revealed and given us a mind to trace out good and necessary consequence, what it means for the Son of God to have taken to Himself human flesh. We may consider four questions, the answers of which bring us near to the reasoning of truth which rose above and beyond the human flaws at that historic moment.

Those four crucial questions are as follows:

(Q1.) Whether there was no hypostatic union but a human person, Christ, distinct from the divine Son.

(Q2.) Whether the hypostatic union was a union of two natures into one.

(Q3.) Whether there is only the divine mind or will of the Son in the incarnation.

(Q4.) Whether we can attribute to the one Christ all that is true of each of the two natures.

The reader will notice how the first two take opposite sides of the main controversy.

Q1. Whether there was no hypostatic union but a human person, Christ, distinct from the divine Son.

One may speak of a union in a few words and yet deny it in additional words. To suppose that Jesus represented a human person distinct from the divine person of the Son who always was—this was the very error that would be called Nestorianism. It posits “two Sons” such that there are two separate persons: one in eternity and the other in time. The problem with this can be seen when considering texts in which Jesus Himself references His own deity. When He says, for example, “before Abraham was, I am” (Jn. 8:58) or “I and the Father are one” (Jn. 10:30), who exactly is He speaking for when He says “I”? Who is He speaking about when He says “I”? If your answer to the second question is different than the first, you will have to help me understand how you got there. If, on the other hand, your answer is the same for both, then one Christ, one divine Son, is the acting Subject and Speaker, and yet there He was in human flesh speaking. It must be that the Person speaks for Himself as Man to men.

Modern liberalism had pressed the “human-ness” of Jesus for various reasons. The first wave came in the nineteenth century. It was precisely the historical that orthodox theologians had ignored in the dogmatic, “pre-critical,” age. The second wave came in the twentieth century, especially after World War II, after which New Testament scholarship fixated upon absolving the early Christian faith of any hint of anti-Semitism. Riding the crest of both waves were a series of “quests for the historical Jesus,” which always meant discovering a more earthy, humble, Jewish, and fallible Jesus that could untie the perceived knots involved in making of Him two supposedly incompatible natures. A Neo-Nestorianism was really only a matter of time.

Q2. Whether the hypostatic union was a union of two natures into one.

In a detail easy enough to miss in Mere Christianity, C. S. Lewis described the incarnation by saying, “supposing God became man—suppose our human nature which can suffer and die was amalgamated with God’s nature in one person—then that person could help us.”3 Lewis was quite right to stress the redemptive purpose of the human nature being assumed. However, the word “amalgamation” is risky at the very least. I do not think Lewis was a closet monophysite; but when this word amalgamation is ordinarily used, the context is either metals combining or groups of people assimilating into a larger culture. On the other hand, the word can simply mean a “unity” between this and that. I draw this out only to make the point that precise words matter all the more when the most important mysteries must be preserved.

The hypostatic union cannot be of two natures into one nature. That would imply a new nature: a third nature. Then this third nature would be neither divine nor human. As the definition at Chalcedon expressed that the Son is now “recognized in two natures, without confusion … the distinction of natures being in no way annulled by the union.” Aquinas concluded from this very statement that, “Therefore the union did not take place in the nature.”4 This conclusion was in answer to two questions that were really asking the same thing from two opposite angles: whether the union took place in the nature (III.2.1) or in the person (III.2.2). He answers in the latter.

Calvin insisted upon the very same doctrine:

When it is said that the Word was made flesh, we must not understand it as if he were either changed into flesh, or confusedly intermingled with flesh, but that he made choice of the Virgin’s womb as a temple in which he might dwell. He who was the Son of God became the Son of man, not by confusion of substance, but by unity of person.5

The most difficult objections to answer regard our conception of what it means to be a person. In our experience, “person” and the natures that go with that person are logically coextensive. In fact, in the Thomistic view of the human person—soul and body unities—it is essential that they are logically coextensive. So there is more than a mere conception that forms an obstacle for us here. There seems to be a real logical conundrum. However, the trouble is that our logic is misapplied to begin with.

From the truth that All human persons are soul-body unities, it does not necessarily follow that All soul-body unities must be, purely and simply, human persons in the logically coextensive sense attributed to us. We may protest that it was necessary that Christ took on our nature. Indeed, it was. But the protest is an equivocation, for we were just now talking about persons in total and not natures per se.

Such were the difficulties in an objection fielded by Aquinas. He works from the definition of person by Boethius: “an individual substance of rational nature.” Simply add the premise that Christ’s human nature was of “a rational soul,” and the inference seems to follow that either such must be a distinct person (Nestorianism) or such must have combined with the divine nature into a new unity (Monophysitism). Thomas’s initial rejoinder is straightforward: “I answer that, Person has a different meaning from nature.” This goes to the heart of what the words “hypostatic union” together mean.

In the particular reply to that objection Thomas adds that,

because human nature is united to the Word, so that the Word subsists in it, and not so that His Nature receives therefrom any addition or change, it follows that the union of human nature to the Word of God took place in the person, and not in the nature.6

In other words, to say it took place in the Person is to affirm that the human nature was assumed by an eternally divine Person who shares one divine nature with the Father and the Son. So the divine nature, or essence, is what is one between Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. What is proper to the Person of the Son is what made it fitting for Him to take on flesh, rather than the Father or the Spirit. But in the incarnation, that union was a union of two distinct natures: divine and human.

Q3. Whether there is only the divine mind or will of the Son in the incarnation.

We deny against the Apollinarians and Monothelitists.

Apollinarius lived at the beginning of the century prior. He taught that the only mind in Christ is that of the eternal logos. Thus some colorful author once called this the “God-in-the-bod” heresy. The idea was that by something like remote control, the divine logos took to Himself a human body and set it into motion. Apollinarius wanted to avoid Docetism—that the whole human nature was a mere “appearance”—though he had to deny the immaterial dimension of that humanity, namely the rational soul.

One reason why this matters can be seen in attempting to resolve the words of Jesus in Matthew 24:36. There we are confronted with something Jesus did not know. Yet the eternal Son is omniscient. There can be no Apollinarian resolution to this. We will see how exactly to resolve this in our fourth question. But if there were no other reason why this matters, it would matter for the average believer in their confidence about the authority of Scripture and deity of Christ. Both would be undermined if all we were left to do with Matthew 24:36 is to conclude that Jesus was involved in either error or deception. It turns out there is another reason why rejecting Apollinarianism matters. However, in order to see this, it will be useful to introduce the other error that denies an aspect of the soul to the human Christ.

Monothelitism is so named because it posits “one” (mono) “will” (thelema) to Christ. This fails for the same reason as the denial of Christ’s human mind. This is to deny the human nature. There are two initial reasons to affirm that Christ had a human will. The first is that will proceeds from mind, as Jonathan Edwards famously defined the will as “that by which the mind chooses any thing.”7 The second is that the human will stands in need of redemption, as John of Damascus put it,

He in His fullness took upon Himself me in my fullness, and was united whole to whole that He might in His grace bestow salvation on the whole man. For what has not been taken cannot be healed.8

The words of Jesus in the Garden of Gethsemane have been pointed to more than any other passage for this truth. There He prayed, “My Father, if it be possible, let this cup pass from me; nevertheless, not as I will, but as you will” (Mat. 26:39). The human will submits to the divine will. Our problem is that we did not submit to the divine will. Calvin makes an important statement about how this passage can help us in understanding the Person of Christ: “Let us, therefore, regard it as the key of true interpretation, that those things which refer to the office of Mediator are not spoken of the divine or human nature simply.”9 In other words, the Hypostatic Union has the design of redemption in mind. The human will of Christ stood in our place. He submitted to God, in one sense, because we had not done so.

Q4. Whether we can attribute to the one Christ all that is true of each of the two natures.

We distinguish.

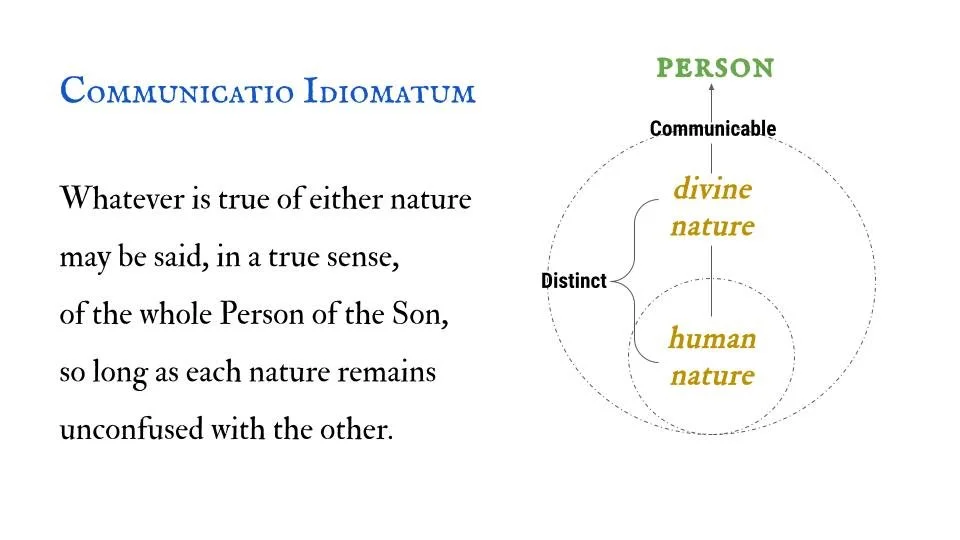

Above I offered more of a concise etymological definition of the Latin expression, communication idiomatum—namely, the communication of properties. But that is not exactly a definition. Let us then consider the following formulation:

Whatever is true of either nature may be said, in a true sense, of the whole Person of the Son, so long as each nature remains unconfused with the other.

In our doctrine of Christ, the concept becomes a tool or method for understanding. Many Christians who have never heard of it nevertheless assume its logic all the time when they correctly parse out truths in various readings of Scripture. Three passages will provide useful illustrations of this. Consider Acts 20:28, 1 Corinthians 15:28, and Matthew 24:36.

In the first passage we read the words of Paul to the Ephesian elders.

Pay careful attention to yourselves and to all the flock, in which the Holy Spirit has made you overseers, to care for the church of God, which he obtained with his own blood (Acts 20:28).

Needless to say, God does not bleed. The divine nature is incorporeal: “God is spirit” (Jn. 4:24). Again, many Christians who have never heard of this Latin phrase, nor worked out the exact logic, can see clearly enough that Paul is implicitly referencing not the divine nature but rather the human nature of Christ. It is Christ’s blood by which God has purchased the church. Why then does Paul not simply say so? However we answer the exegetical question, the mode of our prior reasoning about the two natures will have been what the communicatio describes.

In the second passage, Paul is unpacking to the Corinthians that order to the reign of Christ, in which all enemies are defeated and then glory has been given. He then adds a qualification.

When all things are subjected to him, then the Son himself will also be subjected to him who put all things in subjection under him, that God may be all in all (1 Cor. 15:28).

Those who teach the eternal subordination of the Son to the Father naturally include this passage in their arsenal of proof texts. In order to see how the orthodox position leans heavily upon the communicatio here, consider another text that might seem at first to teach the subordination of the Son. A few chapters earlier, Paul had said, “the head of Christ is God” (1 Cor. 11:3). Here one may easily say that the title “Christ” is naturally predicated of the human as to nature, and the mission of the Son as to transient operation (as opposed to immanent operation). Such cannot be done with 1 Corinthians 15:28 without one additional step. That additional step is what theologians call communicatio idiomatum. Does one have to invoke the words to perform the logic? No. But it will be precisely its logic that such a right mind will have performed.

Then with Matthew 24:36, we need not and must not appeal to divine accommodation—namely, that Jesus knew the whole of the matter in such a way that this was a way of concealing it from His disciples. There were any number of ways for Him to communicate that this is what He was doing. The basic problem with that solution in this case is that it involves Jesus in a falsehood. He said that the Son did not know the thing. The average Christian can understand what is meant, at first, that Jesus was referring in particular to His human nature.

Moving one step further, the Christian who understands why the error of Apollinarianism is an error, will recall that Jesus possesses a distinct human mind. In these two steps, this average Christian has answered rightly, and yet one problem remains. Jesus does not specify His human nature in so many words. The implication demands the truth that the communicatio idiomatum formulates. What is true about the Son per se remains true even if it is only true of the human nature, and not at all true of the divine nature.

Another example is where Paul speaks of the rulers of this world, who “crucified the Lord of glory” (1 Cor. 2:8). We call that error which supposed the Father to have suffered in like manner to the Son, patripassionism. If the impassible God cannot suffer, it is in the Son’s divine nature that He could not suffer, and thus to have crucified “the Lord of glory” has reference to the human nature properly, yet the Person of the Son by communication of the relevant properties.

The question of whether Mary may be referred to as the “God-bearer” (theotokos) is implicit here, and, in fact, Cyril especially called out Nestorius for his insistence on calling Mary simply “Christ-Mother” or “Mother-of-the-Man.”10

Turretin would address this very question.

The “Son of the living God” cannot be called the son of Mary according to that in which he is the Son of God. But because he assumed the human nature from her into unity of person, he is rightly and truly called also the son of Mary in this respect. Thus Mary can truly be called theotokos or ‘mother of God,’ if the word ‘God’ is taken concretely for the total personality of Christ consisting of the person of the Logos (Logou) and the human nature (in which sense she is called ‘the mother of the Lord,’ Lk. 1:43), but not precisely and abstractly in respect of the deity.11

Calvin mentions the Greek term more anciently called idiōmatōn koinōnia, yet he teaches the same doctrine where he says, “For we maintain, that the divinity was so conjoined and united with the humanity, that the entire properties of each nature remain entire, and yet the two natures constitute only one Christ.”12

Calvin then proceeds to make an analogy that is fairly uncontroversial, unless, that is, any reader forgets or altogether ignores what he is doing.

If, in human affairs, any thing analogous to this great mystery can be found, the most apposite similitude seems to be that of man, who obviously consists of two substances, neither of which however is so intermingled with the other as that both do not retain their own properties. For neither is soul body, nor is body soul. Wherefore that is said separately of the soul which cannot in any way apply to the body; and that, on the other hand, of the body which is altogether inapplicable to the soul; and that, again, of the whole man, which cannot be affirmed without absurdity either of the body or of the soul separately.13

Again, this is not an analogy of the divine, as the only immaterial dimension to Christ, to our soul as the immaterial thing. The analogy is very specifically the soul-body unity-distinction in us versus the two natures unity-distinction in the Son. The analogy applies only to the natures being attributable to one unity to whom they belong without confusing one nature with the other. If we can do this about my body and soul, or your body and soul all the time, without supposing that there is a logical contradiction involved, the same must apply to the Son.

__________________________________________________________

1. John Anthony McGuckin, Introduction to St Cyril of Alexandria, On the Unity of Christ (Crestwood, NY: St Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1995), 30.

2. The late nineteenth century discovery of the Syriac MS of Nestorius’s Bazaar of Heracleides is what has caused reassessment about Nestorius’s orthodox credentials, even potential full agreement with the Chalcedonian Definition.

3. C. S. Lewis, Mere Christianity (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1996), 60.

4. Thomas Aquinas, Summa theologiae, III.2.1.

5. John Calvin, Institutes, II.14.1.

6. Aquinas, Summa theologiae, III.2.2.r1.

7. Jonathan Edwards, The Freedom of the Will (Orlando: Soli Deo Gloria, 1996), 1.

8. John of Damascus, On the Orthodox Faith, II.6

9. Calvin, Institutes, II.14.3.

10. Cyril, Unity of Christ, 52.

11. Francis Turretin, Institutes, II.13.5.18.

12. Calvin, Institutes, II.14.1.

13. Calvin, Institutes, II.14.1.