Turretin on the Satisfaction of Divine Justice

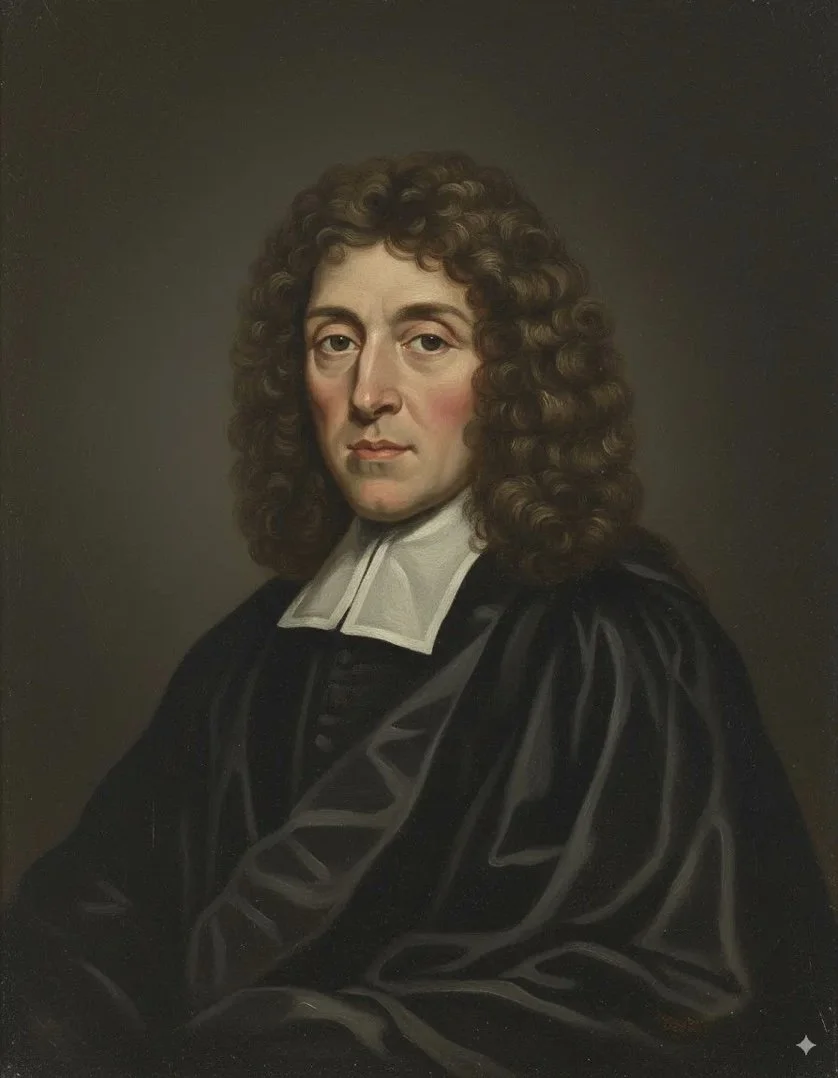

It is not as though John Owen was the only noteworthy Reformed theologian in the late seventeenth century arguing for a particular redemption against various degrees of universalism. One important section of Francis Turretin’s Institutes of Elenctic Theology (1679-85) sets forth the foundation to that doctrine in the idea of Christ satisfying divine justice by the cross. The word “satisfaction” is, like so many other crucial theological terms, not in the Bible.

If a word about such a central topic is not a Bible word, why use it? What exactly does it mean and why is it used as it is in the context of Christ’s work? We must first consider what exactly is being satisfied.

The word has the justice or righteousness of God as its immediate object. These two English words are one in the Greek (δικαιοσύνη), while in Hebrew they are divided between that which is right in God essentially or in action (צְדָקָה) and that which pertains to the imperative, or perhaps codified, expressions of the same (מִשְׁפָט).

Whatever else sin is, in relation to God Himself, our sin puts us out of right relationship—or “rectitude,”1 as Anselm preferred—both legally and personally. The notions of sin as lawlessness, treason, adultery, and the like, are more closely related than many think. Therefore, to speak of Christ’s work satisfying God’s justice is to at least speak of a recompense in the negative sense of undergoing the consequences for what sin deserves. As Turretin succinctly put it,

Satisfaction has God for its object; remission has men. Satisfaction is made to the justice of God and on that account sin is freely remitted. Thus justice and mercy kiss each other, while the former is exercised against sin, the latter towards sinners.2

In Volume II, Topic 14, Questions 10 through 14, under Christ’s mediatorial office—there being two “principal parts” to Christ’s priestly office: satisfaction and intercession—Turretin treats satisfaction under five heads (1) its necessity, (2) its truth, (3) its perfection, (4) its matter, and (5) its object. Here I will only review his section on the necessity (Q.10) and the truth (Q.11) of satisfaction.

The Necessity of the Satisfaction

As there have been several models of the atonement throughout church history, so, more specifically, there have been multiple notions of “satisfaction,” even among those who will use the same term yet mean diverse things by it. This falls back on whether such a thing is necessary to begin with. The Socinians, for example, “not only deny that Christ satisfied for us, but also affirm that it was not at all necessary, since God both could and would gratuitously remit sin without any satisfaction.”

Two other views spoke of a necessity, yet the first meant a hypothetical necessity—i.e., not “necessary absolutely because if God had wished, there were other modes of liberation possible to him.” On the other hand, it was still fitting “that satisfaction should be made to divine justice that [God’s] commands may not be said to have been violated with impunity.” Then there was what Turretin regarded as the most orthodox view:

that of those affirming … its absolute necessity, so that God not only has not willed to remit our sins without a satisfaction, but could not do so on account of his justice. This is the common opinion of the orthodox (which we follow).3

He further argued that there is a fourfold necessity of satisfaction, having “reference either to sin, for which a satisfaction is required; or to the satisfaction itself which is to be made; or to God, to whom it is to be rendered; or to Christ, by whom satisfaction is made.”4 These are a unity. One might even say that these four are a system that is irreducibly complex. Their reasons are mutually interdependent, with the character of God being chief among them.

In order to be more precise, Turretin offered six reasons which prove that a satisfaction was necessary. Although it is not an absolute necessity to the very being of God—God alone qualifies for that distinction—yet, given the decrees of creation and redemption, satisfaction is a consequent necessity: (1) by the justice of God; (2) by the nature of sin; (3) by the sanction of the law; (4) by the preaching of the gospel; (5) by the greatness of God’s love; and (6) by the glory of the divine attributes. Divine justice is in the primary position here, as it is essential to God, and this of absolute necessity. Consequently, “its exercise must be necessary on the supposition of sin, although it becomes free by an intervention of the will.” How is that a matter of freedom? Turretin later adds, “it necessarily demands the infliction of punishment either on the sinner himself or on the surety substituted in his place.”5 In short, what is necessary is that justice be done; what is free includes, at least, the exact object taking on such punishment.

The Truth of the Satisfaction

I mentioned that there were other conceptions of satisfaction. There are four aspects in view, whether or not these may be divided according to different views. First, there was perceived a satisfaction of will rather than of justice, “by which Christ may have fulfilled all the conditions imposed upon him by the divine will in order to procure our salvation ... Second, ... a metaphorical satisfaction which is effected by the balancing of the account of the injured party, which precariously obtains some favor through the mere indulgence of God.” Third, it was supposed Christ could make satisfaction “advantageously” rather than “substitutively.” In other words, He could provide a “satisfactory” foundation for which meeting the condition of faith is the actualization.

Finally, the question is not whether Christ is our Savior either on account of his doctrine announcing to us the way of salvation or on account of the example of his life. He confirmed it by both his virtues and his miracles. Or on account of the communication of his efficacious power, because he will assuredly bestow on us this salvation in his own time.6

Against such fractional views, Turretin offers seven arguments for the work of Christ being a satisfaction of God’s justice against sin: 1. By the redemption of Christ; 2. Because Christ died for us; 3. Because He bore our sins; 4. From the sacrifice of Christ; 5. From our reconciliation with God; 6. From the nature of Christ’s death; and 7. From the attributes of God.7

When one puts all of these together, the result is a work of Christ that is both actual and particular. In other words, Jesus Christ, by His own work and with nothing added, saved His people from their sins (Mat. 1:21).

This is the principal reason that the hypothetical universalist view represents a departure from the whole notion of penal substitutionary atonement. What theologians like Owen and Turretin had insisted upon was that the Bible speaks about the work of Christ on the cross as having a direct, causal effect upon the elect, out of which all of the benefits of Christ flow. That includes all those dimensions belonging to the secondary causality wrought by the Spirit’s work in applying the redemption. In short, that includes the performing of the condition of faith. The constant repetition of the importance of this condition, within the system of Baxter for example, is of no effect here. Either Jesus Christ paid for all of the sins of His people, or else there remains some other way of satisfaction.

It may still be asked why satisfaction cannot be affected by conversion, or, in other words, our faith. Turretin answers with characteristic thoroughness:

The objection of our opponents amounts to this—‘that this reconciliation is effected by our conversion to God and not at all by appeasing the divine wrath because God is not said to be reconciled by us, but we are reconciled to God; nay, he is said to procure for us this reconciliation, which is a sign not of enmity, but of friendship.’ Many arguments refute this capital error ... (1) Scripture sets forth a twofold enmity and alienation … [Rom. 1:18, 30; Col. 1:21; Eph. 2:1; Hab. 2:13] ... (2) If reconciliation was nothing but conversion, then it should rather be said to proceed from Christ’s glorious life than from his bloody death and no reason can be given why sanctification should be proposed by the apostle as the end of our reconciliation (Col. 1:22), since nothing can be the medium and end of itself. (3) Such a reconciliation is meant as is effected by ‘not imputing to us our sins,’ on account of their having been imputed to Christ (since he was made sin for us, 2 Cor. 5:18, 21) and by the substitution of Christ in our place that he might die for us ... (4) Reconciliation is effected by making peace through the blood of his cross (Col. 1:20) and by an atoning sacrifice (hilasmon, 1 Jn. 2:2). But this does not intimate mere conversion, but primarily the appeasing of the wrath of God (which is brought about by the death of a victim).8

Much of the same logic would apply to the more modern objection of biblical scholars, who attempted to minimize the notion of appeasement of God’s wrath, whether by minimizing wrath itself [e.g., C. H. Dodd] or by conflating propitiation with expiation. This is not such an obscure point. Any model which wants to have sin removed without being dealt with is really in the same boat. So he wrote,

In vain is it added that ‘Christ is called our propitiation (hilasmon) and expiatory (hilastērion) sacrifice, not because he appeased God (angry with us) but because he testified that he was already appeased and by no means angry with us.’ The blood of Christ was not shed to prove the remission of sin, but to obtain it, as was the case in the propitiatory sacrifices of the Old Testament dispensation. Otherwise, there would have been no need of Christ to die and to shed his blood, since this could have been sufficiently testified both by his doctrine and by his life.9

Without yet addressing the extent of the atonement in an explicit way, this foundational category of satisfaction already commits one to a “Godward” dimension of Christ’s sacrifice—“a fragrant offering and sacrifice to God” (Eph. 5:2)—as well as a direct effect on the elect for whom Christ made satisfaction. Our sins were in fact placed upon Him (1 Pet. 2:24) and punished in Him (2 Cor. 5:21). One may work out a doctrine of it later, but even the simple faith that cannot spell it out is still a belief, a personal trust, in an accomplishment that Christ performed, and not in a mere provision that lies dormant before all. For Jesus to say from the cross that it was “paid in full,” which is the sense many commentators make of the Greek Τετέλεσται, for “It is finished” (Jn. 19:30) is to speak of that payment that has been fully satisfied.

______________________________________________

1. cf. Anselm of Canterbury, The Major Works (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998). His most basic definition concerns truth as rectitude in On Truth, 9, when a proposition “signifies that what is is.” Works, 163. Further, “this rectitude is the cause of all other truth and rectitude but nothing is the cause of it.” Works, 164. He begins to apply this concept of rectitude to justice in other writings. In his work On the Fall of the Devil, 3, “the angels that loved the justice that they had, rather than the more that they did not have, received as reward in justice that good their will renounced out of love and justice, and they remained in secure possession of what they had.” Works, 198.

2. Francis Turretin, Institutes of Elenctic Theology, II.14.11.26 (Phillipsburg, NJ: Presbyterian & Reformed Publishing, 1994), 436.

3. Turretin, Institutes, II.14.10.4.

4. Turretin, Institutes, II.14.10.5.

5. Turretin, Institutes, II.14.10.17.

6. Turretin, Institutes, II.14.11.2, 3, 4, 5.

7. Turretin, Institutes, II.14.11.6-23

8. Turretin, Institutes, II.14.11.18.

9. Turretin, Institutes, II.14.11.21.