Who and What are God’s People?

But you are a chosen race, a royal priesthood, a holy nation, a people for his own possession, that you may proclaim the excellencies of him who called you out of darkness into his marvelous light. Once you were not a people, but now you are God’s people; once you had not received mercy, but now you have received mercy.

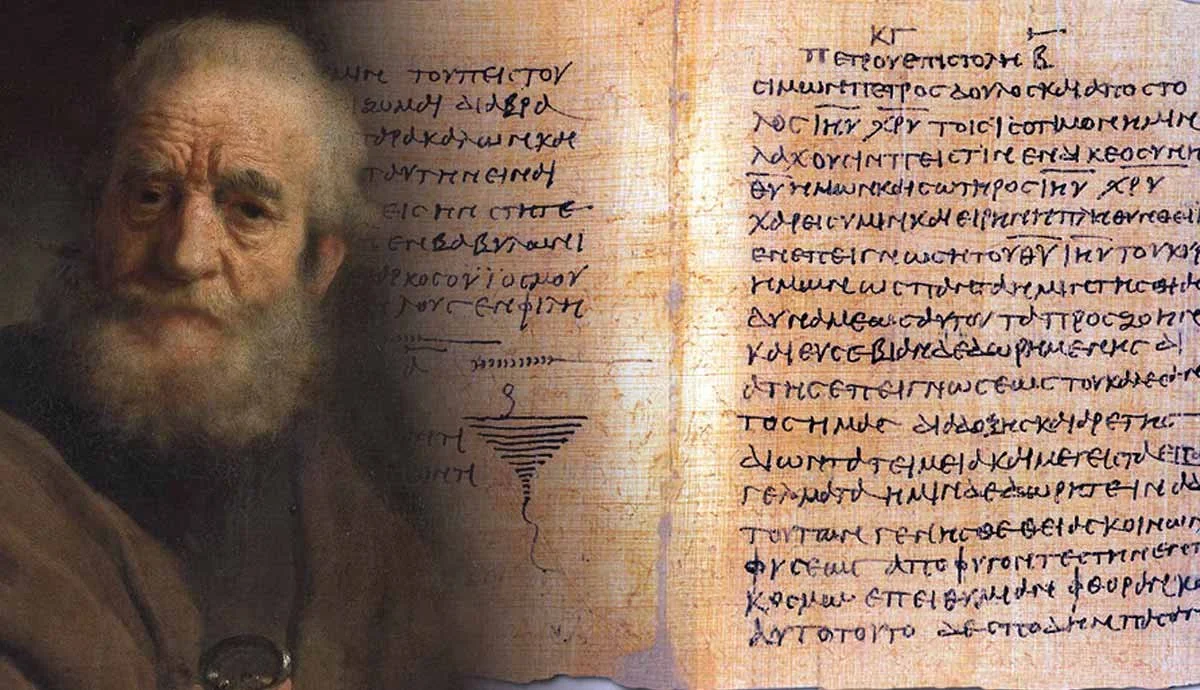

1 Peter 2:9-10

One of the more prevalent little sayings over the past ten years in our culture is found in the three little words: Check your privilege. I won’t go into all of the meanings of that and the assumptions behind it. But I do want to challenge one assumption about privilege that this putdown clearly does assume. That is, that privilege, in and of itself, is bad. A more ungrateful sentiment could hardly be imagined. There is no greater privilege that the one Peter commends here.

Doctrine. The church universal became the people of God to proclaim the excellencies of God.

(i.) The identity of God’s people.

(ii.) The calling of God’s people.

(iii.) The privilege of God’s people.

The centrality of the church—even the life of the local church—is under severe strain today. The younger generation has long been fed up with their parents’ and grandparents’ compromise with the reigning cultural gods of liberalism. The only people who can afford to tell the truth are banished from the church for their troubles. Any claims that God is moving history, right now, through the church will be a difficult sell. Yet if the Bible casts this vision, the first step toward our repentance and re-casting the vision for that lost generation is to believe it ourselves, to understand it in its fullness.

The Identity of God’s People

Where in the Bible have we heard this language before that Peter is using? ‘But you are a chosen race, a royal priesthood, a holy nation, a people for his own possession’ (v. 9a). It first comes to the people of Israel, through Moses, on Mount Sinai.

you shall be my treasured possession among all peoples, for all the earth is mine; and you shall be to me a kingdom of priests and a holy nation’ (Ex. 19:5-6).

Israel was the ‘chosen’ people of God: “The LORD your God has chosen you to be a people for his treasured possession, out of all the peoples who are on the face of the earth” (Deut. 7:6); and “For the LORD has chosen Jacob for himself, Israel as his own possession” (Ps. 135:4). Now he appropriates this language to the entire church of Jews and Gentiles. This has ignorantly and uncharitably been called “Replacement Theology” by modern dispensationalists. This is slanderous nonsense. Not a single believing Jew is being replaced—not one in either Old or New, so long as they, as much as we, believe in Jesus Christ. It remains true, then, “that the Gentiles are fellow heirs, members of the same body, and partakers of the promise in Christ Jesus through the gospel” (Eph. 3:6).

This is further supported by the words of the next verse: ‘Once you were not a people, but now you are God’s people’ (v. 10a). We will come back this verse, but for now, just notice the language that elsewhere the New Testament appropriates to the inclusion of the Gentiles:

even us whom he has called, not from the Jews only but also from the Gentiles? As indeed he says in Hosea, “Those who were not my people I will call ‘my people,’ and her who was not beloved I will call ‘beloved.’” “And in the very place where it was said to them, ‘You are not my people,’ there they will be called ‘sons of the living God’” (Rom. 9:24-26).

The other two expressions are both paradoxes that mix the sacred and the secular. That is not often commented upon. Why does “royal” (βασίλειος) not modify “nation” (ἔθνος), so that the governmental adjective goes with the political noun? And why does “holy” (ἅγιος) not modify “priesthood” (ἱεράτευμα), so that the spiritual adjective goes with the religious noun? But Peter does not do that. He switches them. He mixes the sacred and the secular. However, I actually do not prefer to use the word “mixing” for this, because I do not think this is unnatural at all. John puts the civic and religious together in saying that Jesus “made us a kingdom, priests to his God and Father” (Rev. 1:6). They are even united in the same breath. This is a reflection of the One who is King and Priest supreme, as the prophet said,

It is he who shall build the temple of the LORD shall bear royal honor, and shall sit and rule on his throne. And there shall be a priest on his throne, and the counsel of peace shall be between them both (Zech. 6:13).

Like King, like kingdom; like High Priest, like priesthood. The people of Jesus take on His character, specifically here by uniting their religious and civic life. They do not dishonor their King and High Priest, Jesus, by splitting these apart, and calling one “dirty” or relegating the other to “Sunday only.” They are a whole-life people of God.

The Calling of God’s People

This has two parts, the first religious, the second ethical—these two parts corresponding to the two tables of the law. One is Godward, the other manward. First, there is our call that is directed toward, or, I should say, directs others toward God: ‘that you may proclaim the excellencies of him who called you’ (v. 9b). The first of these two parts has immediate reference to God. These are the praises of Him.

This matches the specific calling of that priesthood. The priests had charge over the corporate worship of the people. At bare minimum, God’s people commend true worship of the true God to everyone they know. These take the same forms as those calls to worship that begin our services: “Come and see what God has done … Come and hear, all you who fear God” (Ps. 66:5, 16). The point is that one of the most basic Christian duties is to reason with all the people we know about their ultimate interest—their urgent need—to be reconciled to God and to honor Him in this life, and with the best of what they have in this life.

I said that there was a second part of this calling, and it is implied by the contrast between light and darkness in the following verse. We are leaving a place behind (darkness) and going toward another (light); but these are not just two locations on a map that guide our lone, individual journeys. We must help each other get out of the one and get toward the other. What is darkness in Scripture? It is not only the dominion of Satan. It is the place where the children of darkness conceive of wickedness. Those who hate the light “have fitted their arrow to the string to shoot in the dark at the upright in heart” (Ps. 11:2).

And this is the judgment: the light has come into the world, and people loved the darkness rather than the light because their works were evil. For everyone who does wicked things hates the light and does not come to the light, lest his works should be exposed (Jn. 3:19-20).

The Bible does not relate the children of light to darkness only as the place we escape from. That would actually be unloving. It gives light an additional duty toward the darkness. As the very presence of holiness exposes sin, so the consistent life of a holy nation exposes the movements of darkness. Paul explains,

Take no part in the unfruitful works of darkness, but instead expose them. For it is shameful even to speak of the things that they do in secret. But when anything is exposed by the light, it becomes visible (Eph. 5:11-13).

It also matches the calling of being citizens of that nation; though that may seem less specified as to “job description” than what a priesthood does. We might think that a nation doesn’t “do” anything—it simply is a group of people. That is typical of a pietistic age in the church, and an individualistic age in the wider culture. In fact, in centuries past, people would have understood a concept that has been called “civic virtue.” In other words, there is a certain stance and there are certain job descriptions of citizens or members of a nation. As to how exactly the church begins to think about that, we will have more to say by way of application.

Above all, this proclaiming of God’s excellencies suggests that the true worship of God and the ordering of our doctrine and life according to who God is, takes precedence over all other concerns. The excellencies of God refer to that which is most excellent—which excel all other things. In fact, all other things derive their worth from something about Him. Any system of doctrine, any philosophy of ministry, any concept of the people of God, that spends its energies exalting other things or hiding in embarrassment the supremacy of God, or the centrality of God, is, to that extent, not a Christian theology or a Christian community. Since the Christian church—Peter is saying here—was founded ultimately to make much of God. This was also the call of Israel of old: “my chosen people, the people whom I formed for myself that they might declare my praise” (Isa. 43:20-21).

The Privilege of God’s People

The call of God here is given a kind of artist’s backdrop: ‘out of darkness into his marvelous light’ (v. 9c). So, the light is the stage or the place that God has called the church into. The imagery hardly needs any defense. It is a natural reaction in all human beings to desire to see and to lament not being able to see. There is also a natural fear associated with the darkness that is relieved by the light.

To become God’s people is to take on His character. John tells us that “God is light” (1 Jn. 1:5), and Jesus says of Himself, “I am the light of the world” (Jn. 8:12). In this light, then, we should not shrink back from what Jesus says about us now: “You are the light of the world” (Mat. 5:14). Like the moon in relation to the sun, we are not the light source, but a light reflector. And yet, it is the greatest thing that a creature could be—to rightly reflect and point everyone in darkness back to the One to whom their souls belong.

The whole of verse 10 is worth looking at again. Yes, this confirms the identity of the people of God. But also a great depth we were rescued from that intensifies the idea of privilege.

Once you were not a people, but now you are God’s people; once you had not received mercy, but now you have received mercy (v. 10).

Privilege of the highest sort is not earned. The highest privilege, by definition, can only be given by One who has all to give and to someone who has nothing to purchase it with.

In one of the other Old Testament passages that displays God’s act of electing a people to be His special possession, we see this same theme:

They shall be mine, says the LORD of hosts, in the day when I make up my treasured possession, and I will spare them as a man spares his son who serves him. Then once more you shall see the distinction between the righteous and the wicked, between one who serves God and one who does not serve him (Mal. 3:17-18).

Our problem is that we do not see this distinction. We do not appreciate this privilege. The reason why we do not appreciate it, first and foremost, is because we take mercy lightly; and we would only take mercy lightly if we took justice and holiness lightly.

This teaches us that being the people of God is a matter of privilege and not a matter of pride. How can this be? In our world of sin, pride and privilege go together. Furthermore, it was this very privilege which had engendered so much of the ethnic pride that had caused Israel to stumble increasingly throughout the Old Testament and then in one final stumbling at the coming of Christ. But they were told,

It was not because you were more in number than any other people that the LORD set his love on you and chose you, for you were the fewest of all peoples, but it is because the LORD loves you (Deut. 7:7-8).

So it is with us. It is “not because of works done by us in righteousness, but according to his own mercy” (Titus 3:5).

Practical Use of the Doctrine

Use 1. Instruction. To be a holy nation in the singular shows the universality of the church. This is an important point. You have heard about the distinction between the invisible church and the visible church; but there is also an easier to understand distinction between the universal church and the local church (or even, at times, the regional church). 1 Peter 2:9-10 is a passage about the universal church. It has implications for the local, but there is a universal truth that it teaches, and it is important to understand how this universal truth is actually specific to the universal church. Now we have to put our thinking caps on here. In his commentary, Sproul gives us the universal side of the coin:

We as Christians are a people without a country. There is never an equation in the Bible between the people of God and a peculiar nationalism. The kingdom of God is not limited to the borders of the United States of America. It transcends every human border.1

That is true about the church universally. However, as we are about to see in coming weeks, in some verses just below, there are certain roles that Christians play within the context of their more local and national boundaries that they do precisely for Christian reasons and within Christian contexts.2 Recognizing these as “Christian ways” of doing these things does not mean that these things become the church. Nevertheless, the point Sproul brings out is important because it prepares us to think above and beyond any of the circumstances of this life and to outlast them, even as a people group. How to walk that out requires distinct studies (classes) on the relevant subjects. You cannot cheat that with a few throwaway lines in sermons. Most people won’t know how you got there.

Use 2. Consolation. Some of the greatest words in the whole Bible are those contrasting words—Once you were this, but now you are something to God, because of God, and so forth: “at one time you were darkness, but now you are light in the Lord” (Eph. 5:8). “And you were dead … But God … made us alive together with Christ” (Eph. 2:1, 4, 5). The reason is that this is something we can mark. This is something we can see the clear difference between what we were, or maybe even how bad things might have been. Here is Peter’s version:

Once you were not a people, but now you are God’s people; once you had not received mercy, but now you have received mercy (v. 10).

This is corporate good news. How fitting that a local church should sing so many songs together that reflect on God’s amazing grace? How unfitting—above all things that are unfitting—for God’s people to set up any system of religion, whether it claims to stretch universally across the word, or whether it is just one local “in-group” that withholds mercy, that burdens the souls of God’s people with the distinctions made by our own excellencies. God’s people make much of God, and there’s no greater privilege than that.

________________________________________

1. Sproul, 1-2 Peter, 52.

2. Compare the contrast between “holy” and “common” societies in David VanDrunen’s Politics after Christendom (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2020) with the rationale for the adjective “Christian” throughout Stephen Wolfe’s A Case for Christian Nationalism (Moscow, ID: Canon Press, 2022). One key usually missing from such discussions is the distinction made by Herman Bavinck between the organic church and institutional church.