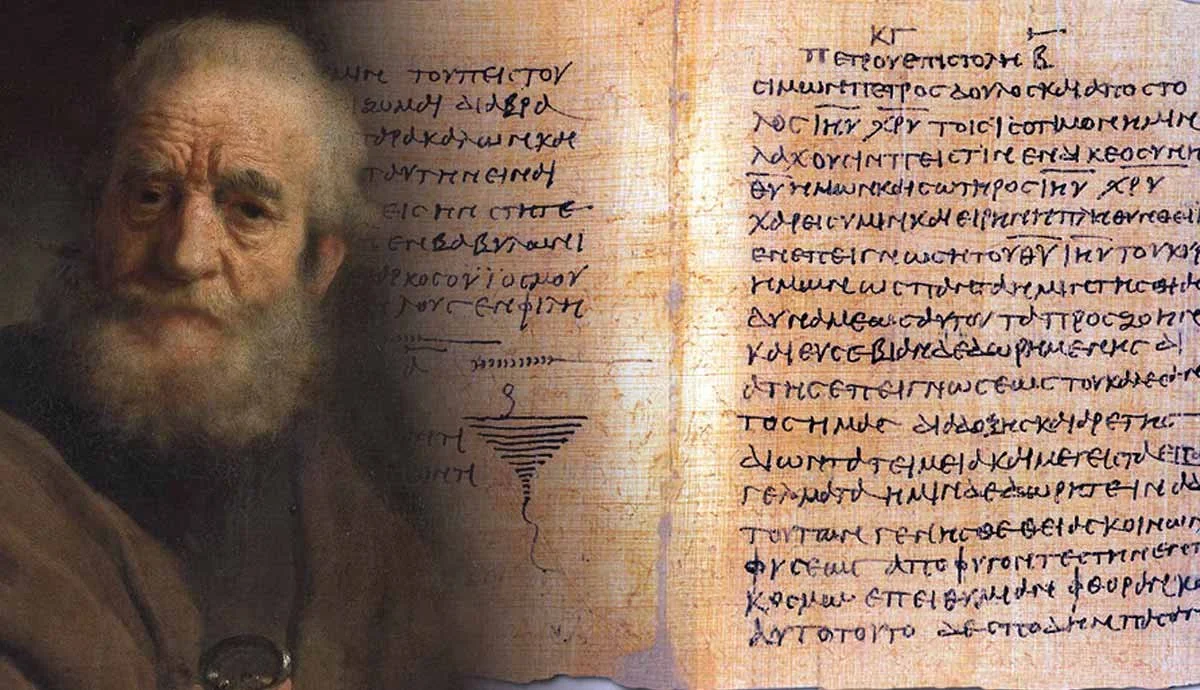

Christian Love

Having purified your souls by your obedience to the truth for a sincere brotherly love, love one another earnestly from a pure heart, since you have been born again, not of perishable seed but of imperishable, through the living and abiding word of God

1 Peter 1:22-23

A few weeks ago I argued from the last passage in Peter’s letter that one of the defining characteristics of modern religion—even modern Christianity—is the attempt to bring God near on our own terms. Another one of the defining characteristics of that religion is really foundational to that previous one. It is the assumption of love. We may not know many things about God or even ourselves, but, as the song says, All you need is love. It is treated as a sacred maxim that we all know what love is. The Bible stands squarely against this. It is precisely that which is most precious that is most twisted by sin.

In his book The Four Loves, C. S. Lewis gave one angle on the problem,

St. John’s saying that God is love has long been balanced in my mind against the remark of a modern author … that “love ceases to be a demon only when he ceases to be a god.” This balance seems to me an indispensable safeguard. If we ignore it the truth the God is love may slyly come to mean for us the converse, that love is God … Every human love, at its height, has a tendency to claim for itself a divine authority. Its voice tends to sound as if it were the will of God Himself.1

This is what Peter’s words in this passage stand against, and help us to get over.

Doctrine. Only what never perishes ever truly loves.

(i.) Christian love flows from purity of heart.

(ii.) Christian love grows only from a new heart.

(iii.) Christian love is shaped by the word in the heart.

Christian love flows from purity of heart.

Peter begins his train of thought with an assumption and moves on to an imperative. First, the assumption: ‘Having purified your souls by your obedience to the truth for a sincere brotherly love’ (v. 22b). Clearly the imperative won’t work on anyone to whom the assumption does not apply. But there is another good reason for this aside from the grammar of the sentence. He qualifies this as brotherly love. Two Greek words come together here. There is one of the words for “love” (φίλος), which is already a friendship or brotherly kind of love, and then for added emphasis the word for “brother” (ἀδελφός). Together, the word φιλαδελφία is used by Peter. Christian love is brotherly love in that all of the objects of this love are siblings in a family that has infinitely deeper roots than those of the flesh of this age.

Then comes the imperative: ‘love one another earnestly from a pure heart’ (v. 22b). This adjective καθαρός means clean, pure, or innocent, goes together with “sincere” or “unfeigned” for a reason. Peter isn’t hauling us back into the court room to show how we have not loved. That’s not a bad question in its place—Have I loved as I ought? However, Peter is cutting to the chase and getting us to it. Brotherly love is pure and gets us to “get to it” by asking a different question: What do we have in common? Then let’s get to work on that together. That will make more sense in a bit when we get down to what Peter says about the Word, so hold that thought.

Christian love grows only from a new heart.

Peter moves from the strength of the affection to its source: ‘since you have been born again, not of perishable seed but of imperishable’ (v. 23a). Four observations about this being born again and its implications for the heart Peter is calling forth: It is a divine action; it is a past action; it is an irreversible action; it is an invincible action.

This being born again is a divine action. Although he does not repeat it here, he had already said it above: “he has caused us to be born again” (1:3). It is in the context of specifically Christian love that John says, “whoever loves has been born of God and knows God” (1 Jn. 4:7).

This being born again is a past action. He says, ‘have been’ here. Jesus gives us this truth in a package that comes with assurance the moment we think about it. He says,

Truly, truly, I say to you, whoever hears my word and believes him who sent me has eternal life. He does not come into judgment, but has passed from death to life (Jn. 5:24).

Having believed, being able to believing, desiring to believe—all pointing to a new birth that has happened. Elsewhere John writes that, “Everyone who believes that Jesus is the Christ has been born of God” (1 Jn. 5:1).

This being born again is a irreversible action. The word ‘imperishable’ means unable to perish. Jesus said that, “everyone who lives and believes in me shall never die” (Jn. 11:26). So no one who comes into this state ever falls out of this state.

This being born again is a invincible action. The ‘imperishable seed’ contains the whole life that cannot perish. That is, it will not and cannot fail to produce anything God means for it to produce. In this case, the specific design God means for it to produce—so says Peter—is this Christian kind of love. If we don’t sense that we have loved as we ought to, we can be sure that God is growing this in us. It is a “fruit of the Spirit” (Gal. 5:22).

Christian love is shaped by the word in the heart.

The last words of Peter here are the ones that could be easy to pass off to the next section about the nature of the word and the gospel in the process of bringing us to life; and so it does do that. However, Peter is deliberately bringing these ideas together—Christian love and the renewing word—so that we have to consider the link between how this seed produces this kind of life and how it forms this kind of love. Remember: imperishable seed. So when he arrives here at this clause: ‘through the living and abiding word of God’ (v. 23b), this is not an afterthought. This isn’t filler. This is Peter giving a crucial cause to this love. The “spiritual DNA” that only the word of God produces is how you get this love, so that without this specific information, you don’t get the same traits and therefore we are not talking about the same life.

The principle is simple: Believe in one reality, and you will become separate from those who believe in a fundamentally different one. Two different visions issue forth in two warring value systems. A word-shaped affection means that we are not talking about a mere flighty feeling here. We are talking about an informed, impassioned state of the soul. This makes all the more sense when the affection in view is brotherly love, and no one that I know of has explained why better than Lewis, in that book on The Four Loves. Whatever one thinks of how he classifies those four Greek words for love, his piece of imagery that he uses for “friendship” or “brotherly” love is pure gold.

In this kind of love [brotherly love], as Emerson said, Do you love me? means Do you see the same truth?—Or at least, “Do you care about the same truth?” The man who agrees with us that some question, little regarded by others, is of great importance can be our Friend.

Lewis goes on to show that this is even reflected on a more private level with hobbies and leisure — two or more people doing something together: “hunting, studying, painting,” etc. “The Friends will still be doing something together, but something more inward, less widely shared and less easily defined. Hence we picture lovers face to face but Friends side by side; their eyes looking ahead.” To bring Lewis together with Peter, this is why you cannot love love into existence: you cannot wish for it anymore than you can wish for friendship in its own right. It has no such rights, by its very nature, and would never ask for it.

The very condition of having Friends is that we should want something else besides Friends. Where the truthful answer to the question Do you see the same truth? would be “I see nothing and I don’t care about the truth; I only want a Friend,” no friendship can arise … There would be nothing for the Friendship to be about.2

This makes perfect sense. Why will the word of God make such a difference in maximizing brotherly love? Because truth tethers the feeling of love to the real good of the beloved. That picture makes it simple. Side by side, looking out at the same reality. The more of the one, real world gets sketched and painted for you and I, together, as one picture, the more that you and I can be a “you and I together.” Where there is no common worldview and mission formation, there can be no fellowship. Although the prophet speaks of providence when he asks: “Do two walk together, unless they have agreed to meet?” (Amos 3:3)—nonetheless people are right to apply this to fellowship, as both providence and friendship see ahead in the relevant senses, and in each, one cannot have the order without the fore-ordering, the savoring without the seeing.

Practical Use of the Doctrine

Use 1. Correction. I said that this brotherly love is a reflection of “infinitely deeper roots” than those of our natural ties in this age. That leads to a controversy where there should never have been one for mature Christians: natural affections or supernatural affections. The Bible teaches both. But it teaches us this in a paradox that you cannot cheat or get around. You must go through it with mental maturity. Jesus calls us to leave behind family ties to follow Him,3 and both He and Paul chastise anyone who dishonors parents or fails to care for their own households.4 So, which is it? And the answer is both, or false—depending on whether we answer positively or negatively. The point is that it is a false dilemma. The resolution in real life is to let grace perfect nature in how we bring our kin into the kingdom. Of course only the Holy Spirit can bring them to life; but we can often bring them to church; and we can always bring them nearer to Jesus by our words and deeds.

Use 2. Exhortation. It is one thing to know that natural relations can be redeemed, but can we redeem the time? In the time that God has left for us, what love will we have left for those who are our spiritual brothers and sisters, and those who are natural kin who we hope to gather to Christ? Let me suggest just three action items to take on with this brotherly—or what should just be the normal definition of—Christian love. Three implications regarding our conversation, our belief-formation, and our long-term building.

Converse only with brotherly love. In your time with others, don’t avoid your eternal souls and your kingdom living now. Small talk is fine until it’s not. If it’s just the spiritual throat-clearing to keep pushing off uncomfortable things, then it’s not loving.

Believe only with brotherly love. In other words, don’t treat Christian doctrine like it is some game to be novel or clever. Treat it as if what you believe for yourself and commend to others has eternal consequences. It has always been legion for young men especially to treat theology as a kind of gentleman’s game. The age of social media—which would be better labeled “antisocial media”—has only made this worse by inflating the promises of winning arguments and posturing with one’s assumed superiority of intellect or even of fidelity to truth. Worse still are those innovations, whether new or old. There is even a “trad-novelty” in our day that has traded in the maxim that If it’s newer, it’s truer, for If it’s older, it’s bolder. Those positions, formerly marginalized as less than orthodox, are now dusted off as yet another piece of information that our Boomer Reformed elders have kept from us. But this is no way to evaluate Christian doctrines. Eternal souls are on the line.

Build only with brotherly love, not meaning a physical building of something, but our long-term, biggest project. What kind of church do we settle for? Especially in light of how relationally disconnected contemporary American life is, and how distorted and poisoned an increasing amount of each generation is. The vast majority of what people do today is paving the way to die alone. Nothing could be further from the spirit of Peter’s words than virtually everything we have been trained to do.

Peter is going to talk about the church in the world in glowing terms in this letter. But how can this be real if we do not even love each other? The Christians of the early centuries confounded the Romans who persecuted them, as one emperor complained, “See how they love each other.” In other words, see how they see themselves as a brotherhood that will outlast this empire. May it be so again.

________________________________________

1. C. S. Lewis, The Four Loves (New York: Harcourt Brace & Co., 1960), 6-7.

2. Lewis, The Four Loves, 66.

3. Matthew 10:34-37; Luke 14:26.

4. Mark 7:9-13; 1 Timothy 5:8.